This document is a translation of Galileo’s “Two New Sciences” from 1914, including introductions and prefaces. The work covers various scientific concepts, including the strength of materials, discussing why larger structures might be proportionally weaker than smaller ones and exploring the force needed to cause breakage. It also examines motion, differentiating between uniform and accelerated motion, and investigates projectile trajectories, identifying their path as parabolic under certain assumptions. Furthermore, the text touches upon acoustics and the relationship between string vibrations and musical intervals, as well as debates philosophical explanations of physical phenomena, such as the cause of acceleration in freefall.

Galileo’s Physics: Strength of Materials and Motion

Based on the sources provided, Galileo’s physics, as presented in his Dialogues concerning Two New Sciences, covers fundamental areas including the strength of materials and the science of motion. This work is considered by Galileo himself to be among the most important of his studies and has been confirmed by posterity as his masterpiece and the foundation of modern physical science. The book is structured as a dialogue between three interlocutors: Salviati, Sagredo, and Simplicio.

Key Areas of Physics Discussed:

The Dialogues are divided into discussions over four days, focusing primarily on two new sciences:

- The science of the resistance of solids to fracture.

- The science of motion (local motion), which includes uniform motion, naturally accelerated motion, violent motions, and projectiles.

The Science of Resistance of Solids to Fracture (First Day)

This part of the Dialogues investigates the strength of materials. Galileo examines why larger structures seem disproportionately weaker than smaller, similar ones.

- Strength and Scale: Observations are made that the strength and resistance against breaking do not increase in the same ratio as the amount of material; for example, a nail twice as big might support eight times the weight.

- Causes of Cohesion: The discussion touches upon what holds the parts of a solid together, considering possibilities like a “gluey or viscous substance” and the role of vacuum. The interlocutors are puzzled by how such a binding force persists in materials exposed to high heat.

- Resistance of Beams and Prisms: Galileo analyzes how the shape and orientation of beams affect their resistance to fracture. He demonstrates that a ruler or prism is stronger when standing on edge than when lying flat, in proportion to its width to thickness. For similar cylinders and prisms, the moments (stretching forces due to their own weight and length acting as a lever arm) bear a ratio that is the sesquiplicate ratio (i.e., power of 3/2) of their lengths. A problem discussed is determining the maximum length a prism can be increased without breaking under its own weight and a load. He also explores what shape should be given to a beam to have constant bending strength throughout its length, identifying a parabolic solid as having this property.

- Strength of Hollow Solids: The discussion also includes the strength of hollow solids, which are used in nature and art to increase strength without adding weight, citing examples like bird bones and reeds.

The Science of Motion (Second, Third, and Fourth Days)

This section, particularly the third and fourth days, is where Galileo lays down the foundations of the science of motion.

- Uniform Motion: Uniform motion is defined as motion where equal distances are traversed in equal time intervals. Key theorems are presented relating distance, time, and speed. For unequal speeds, the time intervals required to traverse a given space are inversely as the speeds. The distance traversed is the product of the speed and the time, or conversely, the speed is the ratio of distance to time.

- Naturally Accelerated Motion: Galileo defines uniformly accelerated motion as starting from rest and acquiring equal increments of speed during equal time intervals. This definition leads to important conclusions about the relationship between distance and time for falling bodies.

- The distance traversed by a body falling from rest is in the duplicate ratio of the time, meaning the distance is proportional to the square of the time.

- The increments in the distances traversed during equal time intervals are to one another as the odd numbers beginning with unity.

- Galileo presents arguments and experiments supporting the idea that falling bodies accelerate and that this acceleration is initially slow, increasing continuously.

- Falling Bodies and Medium Resistance: Contrary to some older ideas (attributed to Aristotle), Galileo’s physics suggests that bodies of the same substance, regardless of weight, move with the same speed in the same medium. Differences in falling speed in a medium are attributed to the resistance of the medium, which affects bodies of different specific gravities or shapes differently. He notes that for heavy, dense bodies falling short distances, the difference in fall times is negligible. He uses pendulum experiments to study the times of descent for bodies of different weights traversing equal arcs, finding their speeds to be equal. The resistance of the medium eventually reduces speed to a constant value for any body falling from rest.

- Motion on Inclined Planes: The time of descent for a body along an inclined plane is related to the time of fall along a vertical line. A significant result is that if a vertical line is the diameter of a semicircle, and an inclined line drawn from the top of the vertical line is a chord of that semicircle, the time of descent along the inclined line is equal to the time of fall along the vertical line. He also investigates the path that allows for the quickest descent between two points. The speed acquired by a body descending along an inclined plane is equal to the speed acquired by falling freely from the same vertical height.

- Projectiles (Violent Motions): Projectile motion is described as a composition of two motions: a uniform horizontal motion and a naturally accelerated vertical motion. Galileo demonstrates that the path of a projectile is a semi-parabola. He discusses how the speed acquired by a body falling from a certain height can be used as a standard to determine the uniform horizontal velocity required to describe a specific parabola. The momentum or speed of the projectile at any point in its parabolic path can be determined. The effect of the medium’s resistance on projectiles is discussed and deemed negligible for practical purposes with fast, heavy projectiles.

Concepts and Methods

Throughout the Dialogues, Galileo employs a mathematical approach, heavily relying on geometry and proportions to define concepts and demonstrate theorems. He contrasts the power of sharp distinction belonging to geometry with logic, which he sees more as a tool for testing arguments rather than stimulating discovery. The text also touches upon abstract concepts like continuous quantities, indivisibles, and the infinite. Terminology, such as “moment,” “speed,” “force,” and “momentum,” is used, sometimes with discussion of their meanings and variations.

Galileo’s Physics of Motion

Based on the provided excerpts from Galileo’s Dialogues concerning Two New Sciences, the physics of motion is a central theme, constituting the “Second new science” discussed over the Third and Fourth Days. This science investigates what Galileo calls “local motion”. The discussion on motion is divided into three parts: uniform motion, naturally accelerated motion, and violent motions or projectiles.

Uniform Motion

Galileo begins by defining uniform motion as one in which the distances traversed by a moving particle during any equal intervals of time are themselves equal. He adds the word “any” to the older definition to emphasize that this equality must hold for all equal time intervals, not just specific ones.

Key theorems regarding uniform motion are presented, establishing fundamental relationships between distance, time, and speed:

- If a particle moves uniformly, the time intervals required to traverse two distances are to each other in the ratio of these distances. This means time is proportional to distance for constant speed.

- If a particle traverses two distances in equal time intervals, these distances will bear to each other the same ratio as the speeds. Conversely, if the distances are as the speeds, the times are equal. This implies distance is proportional to speed for equal times.

- The time required to traverse a given distance at different speeds is inversely proportional to those speeds.

- If two particles move uniformly with different speeds over unequal times, the ratio of the distances covered bears the compound ratio of the speeds and time intervals. This is equivalent to stating that distance = speed × time.

- Conversely, if two particles move uniformly with unequal speeds over unequal distances, the ratio of the time intervals occupied is the product of the ratio of the distances and the inverse ratio of the speeds. This is equivalent to stating that time = distance / speed.

Naturally Accelerated Motion

Following uniform motion, Galileo discusses naturally accelerated motion, such as that of heavy falling bodies. He aims to find a definition that best fits natural phenomena, emphasizing that while one can invent arbitrary motions, the focus here is on motions found in nature.

Galileo proposes a definition for uniformly accelerated motion: it is a motion which, starting from rest, acquires equal increments of speed during equal time intervals. He contrasts this with the idea that speed might be proportional to the space traversed, arguing and demonstrating that this latter idea is incorrect.

A crucial consequence of Galileo’s definition of uniformly accelerated motion is the relationship between distance and time for a body falling from rest:

- The spaces described by a body falling from rest with a uniformly accelerated motion are to each other as the squares of the time-intervals employed in traversing these distances. This means distance is proportional to the square of time (d ∝ t²).

- From this, it follows that if equal time intervals are considered from the beginning of the motion, the spaces traversed during these intervals are to one another as the series of odd numbers (1, 3, 5, 7, etc.). So, in the first time interval, it covers a certain distance; in the second equal time interval, it covers three times that distance; in the third, five times, and so on.

Galileo investigates falling bodies and the effect of the medium’s resistance. He challenges the Aristotelian view that bodies of different weights move in the same medium with speeds proportional to their weights. Through arguments and observations, he suggests that in a medium devoid of resistance (a vacuum), all bodies would fall with the same speed. Differences observed in media like air are attributed to the medium’s resistance, which affects bodies of different specific gravities or shapes differently. Pendulum experiments are used to support the idea that bodies of different weights (but the same substance or specific gravity) traverse equal arcs in equal times, suggesting their speeds are equal when medium resistance is accounted for.

Galileo also analyzes motion on inclined planes. He shows that the speed acquired by a body descending along an inclined plane is equal to the speed acquired by falling freely from the same vertical height. The time of descent along an inclined plane is related to the time of fall along the vertical height, bearing a specific geometrical relationship (if the vertical is the diameter of a semicircle and the inclined plane is a chord from the top, the time of descent along the chord equals the time of fall along the diameter). He discusses how the speed varies with the inclination of the plane, being maximum along a vertical direction and diminishing as the plane diverges from vertical.

The concept of momentum, velocity, impetus, tendency to motion, ability, or energy is used throughout the discussion of motion, particularly in relation to acquired speed and the force of descent. Galileo defines a standard for measuring speed or momentum, often using the speed acquired after falling a certain distance (like the height of a spear) as a reference.

A key idea related to motion on planes is that any velocity once imparted to a moving body will be rigidly maintained as long as external causes of acceleration or retardation are removed, such as on horizontal planes. This implies that motion along a horizontal plane is perpetual if the velocity is uniform, as it cannot be diminished or destroyed.

Violent Motions and Projectiles

The physics of motion culminates in the discussion of violent motions, specifically the motion of projectiles. Galileo describes this motion as a composition of two independent motions: one which is uniform and horizontal, and another which is vertical and naturally accelerated.

By analyzing the combination of these two motions, Galileo demonstrates that the path of a projectile is a semi-parabola. He uses geometry and the previously established properties of uniform and naturally accelerated motion to show how the horizontal distance traveled is proportional to time (due to uniform horizontal velocity) and the vertical distance fallen is proportional to the square of time (due to natural acceleration downwards).

The concept of the composition of momenta or velocities is important here. Galileo states that when the motion of a body is the resultant of two uniform motions (one horizontal, one vertical), the square of the resultant momentum is equal to the sum of the squares of the two component momenta. When one component is uniform horizontal and the other is naturally accelerated vertical, the resultant path is a parabola, and the momentum is always increasing because the vertical speed increases. The momentum at any point in the parabolic path is determined by combining the constant horizontal momentum and the vertical momentum acquired by falling from rest through the corresponding vertical height. The square of the resultant momentum is equal to the sum of the squares of the two components. The momentum acquired at the terminal point of a semi-parabola is equal to that acquired in falling through a vertical distance equal to the sum of the ‘sublimity’ (related to the initial horizontal speed) and the altitude of the semi-parabola.

Galileo acknowledges that the resistance of the air affects projectile motion, altering the ideal parabolic path and causing motion to finally cease. Air resistance offers greater impedance to less dense bodies and increases with the speed of motion. However, for heavy, dense projectiles moving at speeds that are not excessively high, the effect of air resistance is considered small and negligible for practical purposes, allowing the parabolic trajectory to be observed very exactly.

Overall, Galileo’s physics of motion, as presented in these excerpts, moves from precise definitions of uniform and accelerated motion to the analysis of compound motions like projectile motion, using mathematical reasoning and geometrical demonstrations to establish key theorems and properties while considering the influence of external factors like medium resistance.

Galileo on Material Resistance and Strength of Solids

Based on the provided excerpts, the “First new science” discussed in Galileo’s Dialogues concerning Two New Sciences deals with the resistance which solid bodies offer to fracture by external forces. This subject is considered of great utility, especially in the sciences and mechanical arts, and is said to abound in properties and theorems not previously observed or demonstrated.

One of the central findings presented is that when machines and structures are built of the same material and maintain the same ratio between parts, larger ones will not be as strong or as resistant against violent treatment as smaller ones. This means that similar structures are not proportionately strong. Even if the material were absolutely perfect, the mere fact that it is matter means the larger machine will not correspond with exactness to the smaller in strength. There is a necessary limit for every structure, whether artificial or natural, beyond which neither art nor nature can pass, assuming the material and proportion are preserved. Examples supporting this include:

- A long, thin rod that just supports itself will break if a hair’s breadth is added to its length, and a larger rod of the same proportion will also break under its own weight, while shorter ones will be strong enough to support more than their weight.

- A large column might break under its own weight, even while preserving the ratio of length to thickness found in a smaller, intact column made of the same stone.

- Conversely, when decreasing size, the strength of the body is not diminished in the same proportion; smaller bodies have greater relative strength. A small dog can carry multiple dogs of his own size, but a horse likely cannot carry one of its own size. Similarly, a small scantling or marble cylinder will not break when falling from a height that causes a large beam or column to go to pieces. This leads to the conclusion that similar solids do not exhibit a strength which is proportional to their size.

The coherence of materials, which provides this resistance, is discussed as being produced by several causes. In materials like wood and rope, fibers run lengthwise and render the material strong. In materials like stone or metal, the coherence seems to be due to nature’s repugnance which she exhibits towards a vacuum, and potentially a gluey or viscous substance which binds parts firmly together. The force of the vacuum can be demonstrated by attempting to separate two highly polished plates of marble, metal, or glass placed face to face; they exhibit such a repugnance to separation that the upper one can lift the lower one. This resistance is present between the parts of a solid and contributes to their coherence. The force of the vacuum can be measured, for instance, by the weight of a column of water (about eighteen cubits high) that can be sustained by a pump. However, while the vacuum is a sufficient cause for holding two polished plates together, it alone is not sufficient to bind together the parts of a solid cylinder of marble or metal when pulled violently. This suggests the need for another cause. The combined resistance of an extraordinarily great number of exceedingly minute vacua between the smallest parts might, however, provide a significant resistance.

The discussion moves from resistance to a direct longitudinal pull to resistance against bending forces. A solid capable of sustaining a very heavy weight longitudinally is easily broken by the transverse application of a weight. Fracture in a beam fixed at one end occurs at the point where the support acts as a fulcrum for a lever. The magnitude of the applied force at the end bears to the magnitude of the resistance in the thickness of the prism a ratio related to the length of the beam compared to half of its thickness (or the semidiameter for a cylinder).

Several propositions quantify how bending strength varies with the dimensions of prisms and cylinders made of the same material:

- A prism or ruler whose width is greater than its thickness offers more resistance to fracture when the force is applied in the direction of its breadth (standing on edge) than in the direction of its thickness (lying flat). The resistance is in the ratio of the width to the thickness.

- Considering the effect of the prism’s own weight when fixed horizontally at one end, the bending moment due to its weight increases in proportion to the square of the length.

- In prisms and cylinders of equal length but unequal thicknesses, the resistance to fracture (bending strength) increases in the same ratio as the cube of the diameter of the base. Longitudinal resistance depends on the base area (square of diameter), but transverse resistance involves the lever arm of the radius, leading to the cubic relationship.

- For prisms and cylinders which differ in both length and thickness, the resistance to fracture (load they can support at their ends) is directly proportional to the cubes of the diameters of their bases and inversely proportional to their lengths.

Regarding beams supported at both ends, fracture typically occurs at the middle under a central load. If a cylinder is supported at both ends and a force is applied at some point other than the middle, a different force is required to produce fracture. The resistance to fracture at any two points on the beam is in the ratio of the rectangles formed by the segments into which each point divides the total length. This means the prism grows constantly stronger and more resistant to pressure at points more removed from the middle. This suggests that in large heavy beams, a considerable portion near the ends could be cut away to lessen the weight without significantly diminishing strength.

Galileo also discusses the problem of designing a solid that is equally resistant at every point. He demonstrates that if a prism is cut along a diagonal line, one resulting shape grows weaker as it is shortened, while another grows stronger. This leads to the idea that there must be a shape that offers the same resistance at all points. Cutting a prism along a parabola achieves this. This process removes one-third of the volume, reducing the weight by thirty-three percent without diminishing strength, a fact of utility in the construction of large vessels where lightness is important. It is noted in the source that this curve is actually a catenary.

Finally, the strength of hollow solids is examined. These are frequently employed in art and nature (e.g., bones of birds, reeds) to greatly increase strength without adding weight. A hollow lance or tube is much stronger than a solid one of the same length and weight. For two cylinders, one hollow and one solid, having equal volumes and lengths, their bending strengths are to each other in the ratio of their diameters. The hollow tube’s strength exceeds the solid cylinder’s strength in the proportion that its diameter exceeds the solid cylinder’s diameter.

Galileo’s Mathematical Physics

Drawing on the provided excerpts, Galileo’s Two New Sciences deeply explores several mathematical concepts, which are foundational to the physical principles being discussed. The author, referred to as “our Academician,” demonstrates his findings through geometrical methods, suggesting that while some conclusions might have been previously reached, they had not been proven “in a rigid manner from fundamental principles”. Geometry is presented as a powerful tool for “sharp distinction” and stimulation to discovery, potentially surpassing logic in this regard. Euclid’s elements are assumed to be familiar to the reader.

Several key mathematical concepts are woven throughout the text:

- Geometry as the Method of Proof: The entire framework of the discussion relies heavily on geometrical demonstrations. Propositions regarding the strength of materials and the motion of projectiles are proved using figures, lines, ratios, and areas. The discussion even includes specific geometrical problems, such as describing a circle where lines drawn from two points to any point on the circumference maintain a constant ratio.

- The Nature of the Infinite and Indivisible: A significant philosophical and mathematical debate arises regarding how continuous quantities (like lines or solids) can be composed of indivisible quantities (like points). This concept is described as “incomprehensible to us”. An objection is raised that adding indivisibles cannot create a divisible quantity. Galileo addresses this using the idea that while finite numbers of points are limited, lines of different lengths contain an infinite number of points, and one line does not contain more points than another. He draws a parallel between the infinite number of points in a line and the infinite number of “finite parts” that can be assigned to it. The analogy of comparing the number of all integers to the number of squared integers highlights the counterintuitive nature of dealing with infinity. The discussion extends this to argue that bending a straight line into a circle (a polygon with infinite sides) can be seen as reducing the infinite number of points to actuality, similar to how bending into a square actualizes four parts. This concept of indivisibles and the infinite is also used to explain phenomena like contraction without interpenetration of finite parts.

- Ratio and Proportion: These are central to quantifying physical relationships. The strengths of beams, cylinders, and prisms are expressed as ratios of their dimensions, often involving squares and cubes. The times of descent along inclined planes are compared using ratios, including the inverse ratio of the square roots of their heights. Mean proportionals are frequently used in constructions and proofs involving ratios and squares. The concept of sesquialteral ratio (3:2 power) is applied to the relationship between the volume and surface area of similar solids, and the moments of similar cylinders and prisms.

- Powers (Squares, Cubes, Roots): Squares and cubes are used to relate the dimensions of objects to their strength or resistance. The moment of a beam’s weight increases with the square of its length. The resistance of cylinders and prisms to fracture is proportional to the cube of their diameter. The concept of squares and roots also appears in the discussion of infinite numbers.

- Areas and Volumes: Calculations of areas and volumes are used in various geometric proofs, such as demonstrating the equality of a cone and a “bowl” (cylinder minus hemisphere) sliced at different heights. The volume calculation of a parabolic solid is used in the context of optimizing beam shape. The concept of area is also relevant when discussing the surface area of cylinders.

- Conic Sections (Parabola): The parabola plays a crucial role in the discussion of projectile motion. Galileo demonstrates that a projectile carried by uniform horizontal motion and naturally accelerated vertical motion describes a semi-parabola. Properties of the parabola necessary for this demonstration are explicitly proven. A parabolic shape is also suggested for beams to achieve uniform resistance at all points, reducing weight without diminishing strength.

- Trigonometric Concepts and Tables: In the section on projectile motion, concepts related to angles of elevation and their tangents are used to determine the “altitude” and “sublimity” of parabolas describing projectile paths. A table giving altitudes and sublimities based on the angle of elevation for a constant amplitude is provided, demonstrating the practical application of these concepts. The tangent of an angle is explicitly related to the altitude and sublimity in a constant amplitude scenario.

- Mathematical Definitions: The text notes that mathematical definitions are simply the “imposition of names” or abbreviations to simplify communication.

Overall, the sources demonstrate a deep reliance on mathematical principles, particularly geometry and the concepts of ratio, proportion, and powers, to rigorously describe and prove physical phenomena in the emerging science of mechanics and strength of materials. The discussion also touches upon complex foundational issues concerning the nature of continuous quantities and the infinite, highlighting the mathematical challenges inherent in describing the physical world.

The Physics of Sound and Harmony

Drawing on the provided excerpts, the dialogue in Two New Sciences delves into the realm of acoustics and sound, presenting explanations for musical phenomena based on the properties of vibrations and ratios. This discussion is treated as a “splendid subject”, and the “Author” (referred to as “our Academician”) has thought much upon it and demonstrated his findings.

Here are the key points discussed regarding acoustics and sound:

- Vibrations as the Source of Sound: The fundamental idea is that sound is produced by vibrating bodies. These vibrations cause the surrounding air to vibrate and quiver, creating ripples or pulses that spread through space and strike the tympanum of the ear. The mind then translates this stimulus into sound.

- Experimental Evidence for Waves: Experiments are described to illustrate these vibrations and waves. Scraping a chisel quickly produces a whistling sound, and simultaneous marks left on the surface are closer together for higher pitches and farther apart for lower pitches. Sounding a glass by rubbing the rim produces vibrations and a tone, and if the glass contains water or sits in a vessel of water, regular ripples are seen spreading from it. These ripples visually represent the waves produced by the sound. Feeling the chisel tremble or a shiver in the hand when it hisses, and feeling motion in the throat when speaking (especially low, strong tones), also provides tactile evidence of these vibrations.

- Factors Affecting Pitch: Traditionally, the pitch of a string was related to its length. However, the dialogue points out that while shortening a string to half its length (with constant tension and size) produces an octave (2:1 ratio), changing tension or size yields different relationships. To produce an octave by stretching, the required weight must be quadrupled (ratio of 4:1). To produce an octave by changing size (weight per unit length), the size must be reduced to one-fourth (ratio of 4:1). Similarly, the fifth (3:2 ratio by length) requires a squared ratio (9:4) for tension or size (weight). This leads to questioning why philosophers focused solely on the length ratio.

- Frequency as the True Determinant of Musical Intervals: The crucial insight presented is that the ratio of a musical interval is not immediately determined by the string’s length, size, or tension, but rather by the ratio of their frequencies. This means the ratio of the number of pulses of air waves that strike the ear in a given time.

- Explanation of Consonance and Dissonance: The different sensations produced by combinations of notes (pleasing or offensive) are explained by the regularity or irregularity of the pulses striking the ear drum.

- Dissonance arises from discordant or incommensurable vibrations that strike the ear “out of time”. This keeps the ear drum “in perpetual torment, bending in two different directions”. An example given is two strings with a frequency ratio based on the side and diagonal of a square (an incommensurable ratio), producing a harsh dissonance similar to an augmented fourth or diminished fifth.

- Consonance occurs when pairs of tones strike the ear with a certain regularity. This regularity is due to the pulses delivered by the two tones in the same time interval being commensurable in number.

- Specific Consonances:Unison (1:1 frequency ratio): Vibrations always coincide, acting like a single string, and thus is not strictly called a consonance.

- Octave (2:1 frequency ratio): For every pulse from the lower string, the higher string delivers two. This means at every other vibration of the upper string, both pulses arrive simultaneously. Half of the upper string’s pulses are delivered in unison with the lower string’s pulses. It is described as the principal harmony, very like unison, but perhaps “too much softened and lacks fire” due to the regularity and frequency of coinciding pulses.

- Fifth (3:2 frequency ratio): For every two vibrations of the lower string, the upper one gives three. One-third of the pulses from the upper string strike in unison with the lower. Between each pair of concordant vibrations, two solitary vibrations of the upper string and one solitary vibration of the lower string intervene, separated by equal time intervals. This is described as producing a “tickling of the ear drum” with a mix of softness and sprightliness.

- Fourth (4:3 frequency ratio): Three solitary vibrations intervene between simultaneous pulses.

- Second (9:8 frequency ratio): Only every ninth vibration of the upper string coincides with one of the lower string. The numerous discordant pulses in between produce a harsh effect.

- Pendulum Analogy: The motion of pendulums is used to provide a visual illustration of these concepts. Each pendulum has a definite time of vibration. Suspending pendulums with lengths corresponding to agreeable musical intervals (like 16, 9, and 4 units for vibrations in the ratio 2:3:4, which includes octaves and fifths) shows that their threads cross and align at the same point after a definite number of vibrations, repeating a cycle. If the vibration ratios are incommensurable or return only after a long time/many vibrations, the eye is confused by the disorderly crossing, just as the ear is pained by irregular air waves. Blowing on a pendulum at its natural frequency demonstrates how repeated impulses at the correct timing can build up motion, analogous to how the air waves from one string cause a sympathetically vibrating string to oscillate.

In summary, the discussion in the sources presents a theory of sound and music grounded in the physics of vibrations, emphasizing the critical role of frequency ratios in determining musical intervals and the regularity of air pulses hitting the ear drum as the basis for consonance and dissonance. This is supported by experimental observations and geometric reasoning, moving beyond explanations based solely on string length.

Two New Sciences Quiz and Study Guide

Dialogue Concerning the Two New Sciences Study Guide

Quiz

- According to Salviati, how can one determine the maximum length a wire of a given material can sustain itself without breaking under its own weight?

- What experiment does Salviati propose to measure the resistance of a vacuum?

- How does Salviati explain the ability of a rope made of short fibers to sustain great force?

- What unexpected observation does Salviati make about the relationship between the number of squares and the number of numbers?

- How does Salviati suggest one can distinguish between actual and potential division of a line?

- What does Salviati propose as the reason why hard substances, when reduced to a fine powder, become fluid-like when suspended in a liquid?

- What experiment with a vibrating glass and water does Salviati describe to illustrate the concept of waves produced by a sonorous body?

- According to the source material, how is the ratio of a musical octave explained in terms of string length?

- When considering the bending strength of prisms and cylinders, what type of resistance is the focus of the discussion?

- How does Salviati propose to determine the weight of compressed air compared to water?

Quiz Answer Key

- One can determine the maximum length by fixing one end of a wire and attaching loads to the other until it breaks. By knowing the maximum load supported and the wire’s own weight, one can calculate the length of wire of that same size whose weight equals the breaking load plus the wire’s weight.

- Salviati proposes a device involving a hollow cylinder filled with water and a tightly fitting stopper with an attached wire. By hanging a vessel filled with heavy material onto a hook on the wire until the stopper separates from the water’s surface, the weight of the stopper, wire, and vessel with contents represents the force of the vacuum.

- Salviati explains that while a single fiber can be easily broken by pulling, when many fibers are tightly bound together, as in a rope, they are grasped by the surrounding medium along their entire length, requiring great force to separate them.

- Salviati observes that there are as many squares as there are numbers because every square has a unique root and every root has a unique square, and every number is the root of some square.

- Salviati suggests that bending a straight line into a polygon with a finite number of sides brings those parts into actuality. Similarly, bending the line into a polygon with an infinite number of sides (a circle) makes the infinite number of points actual.

- Salviati suggests that when a hard substance is reduced to a fine powder, it is resolved into infinitely small, indivisible components, which he believes accounts for why they become fluid when suspended in a liquid.

- Salviati describes bowing a viola base string near a goblet of thin glass with the same tone, causing the goblet to vibrate. He also mentions observing ripples spreading in water when a glass containing water is sounded by rubbing the rim.

- The source material explains that an octave corresponds to a ratio of two, meaning that sounding half the length of a string after sounding the full length produces the octave.

- The discussion focuses on the resistance to fracture (bending strength) when a rod is fastened at right angles into a vertical wall, as opposed to its resistance to longitudinal pull.

- Salviati describes two methods, one involving a vessel with compressed air pushing water out, and another involving weighing a vessel with compressed air before and after release, to determine the weight of a known volume of compressed air and compare it to the weight of an equal volume of water.

Essay Format Questions

- Analyze the discussion of finite and infinite division within the text. What are the arguments presented by the characters, and what conclusions does Salviati ultimately draw regarding the nature of continuous quantities?

- Discuss the experiments and reasoning presented in the text regarding the weight and specific gravity of air. How does this discussion challenge or support existing ideas (specifically Aristotle’s), and what methods are proposed for empirical investigation?

- Explain Salviati’s analysis of musical intervals in terms of vibrating strings. How are ratios applied to string length, tension, and size to produce different intervals, and what does this reveal about the relationship between physical properties and perceived sound?

- Examine the concepts of “moment,” “resistance,” and “bending strength” as discussed in the context of the strength of materials. How do these concepts relate to the shape, size, and material of objects, and what principles are derived concerning their ability to withstand fracture?

- Describe the experiments and explanations offered by Salviati concerning the motion of falling bodies and projectiles. How are concepts like momentum, velocity, and trajectory discussed, and what mathematical principles, such as the properties of parabolas, are introduced to describe these motions?

Glossary of Key Terms

- Momenta / Momentum: Used in several senses throughout the text, including force, speed, impetus, ability, energy, and the quantity of motion or effect acquired by a body. Often associated with the capacity to produce an effect.

- Forza: Force, also used in the sense of mechanical advantage or the power of percussion.

- Violenza: Great force, particularly in the context of breaking a rope.

- Vacuum: A space devoid of matter. The text explores the resistance attributed to a vacuum as a binding force.

- Cubits: A unit of length.

- Scantling (corrente): A piece of lumber, smaller than a beam.

- Beam (trove): A larger piece of lumber.

- Resistance (resistenza): The capacity of a material or object to withstand forces, particularly breaking strength or bending strength.

- Resistenza allo strapparsi: Resistance to tearing or pulling apart.

- Corpulenza: Density.

- Levity: The quality of being light; the opposite of gravity.

- Quantita: Quantity, also used to refer to volume.

- Mole e quantita: Volume and quantity.

- Monochord: A musical instrument with a single string, used to demonstrate musical intervals.

- Diapason: The musical interval of an octave.

- Diapente: The musical interval of a fifth.

- Sesquialtera ratio: A ratio of 3:2.

- Dupla sesquiquarta: A ratio of 9:4, which is the square of 3:2.

- Intervals musici: Musical intervals.

- Tuono: Tone or pitch.

- Indivisible: Something that cannot be divided into smaller parts, such as a point.

- Divisible: Something that can be divided into smaller parts, such as a line or surface.

- Infinite, in potenza; e finite, in atto: Potentially infinite, and actually finite. Refers to the state of division.

- Amplitude: In the context of projectile motion, the horizontal distance covered by a projectile.

- Altitude: In the context of projectile motion or parabolas, the vertical height.

- Sublimity: A term used in the context of parabolas, related to the horizontal distance traveled for a certain vertical drop or rise.

- Naturally accelerated motion: Motion in which the velocity increases uniformly with time, such as the motion of a freely falling body.

- Uniform motion: Motion in which the velocity remains constant.

- Parabola: A specific curved shape described by projectiles under the influence of gravity.

- Tangente: Tangent, a line that touches a curve at a single point.

- Mean proportional: A term from geometry where, in a sequence of three numbers (a, b, c), b is the mean proportional if a/b = b/c (or b² = ac).

- Ex aequali in proportione perturbata: A term from geometry referring to a compound ratio derived from a sequence of ratios where the order of the terms is altered.

- Quadrants: In geometry, a quarter of a circle.

- Annulus: The region between two concentric circles.

Briefing on Selected Science and Philosophy

This briefing document summarizes key themes, ideas, and facts presented in the provided excerpts, drawing directly from the text where appropriate. The excerpts primarily focus on concepts in physics and mechanics, presented in a dialogue format between characters named Salviati, Simplicio, and Sagredo.

I. Strength of Materials and Scaling

A significant portion of the excerpts is dedicated to exploring the strength of materials and how this strength changes with scale.

- Scaling and Breaking Strength: A crucial observation is made regarding the inability of larger objects, even if proportionally scaled, to support themselves or external loads in the same manner as smaller ones. This is illustrated with a hypothetical rod that is just able to support its own weight. Salviati states: “…if a hair’s breadth be added to its length it will break under its own weight and will be the only rod of the kind in the world. Thus if, for instance, its length be a hundred times its breadth, you will not be able to find another rod whose length is also a hundred times its breadth and which, like the former, is just able to sustain its own weight and no more: all the larger ones will break while all the shorter ones will be strong enough to support something more than their own weight.” This highlights a fundamental concept of scaling – properties that depend on surface area scale differently than those that depend on volume, leading to limitations as size increases.

- Comparison of Material Strengths: The text explores how the breaking strength of materials can be quantified and compared. An experiment is described to determine the maximum load a wire can sustain before breaking. This allows for the calculation of the maximum length of a wire or rod of that material that can support its own weight. Salviati explains this with a copper wire example, concluding that “all copper wires, independent of size, can sustain themselves up to a length of 4801 cubits and no more.”

- Types of Resistance: The discussion differentiates between different types of resistance to fracture. Two main types are mentioned: resistance to longitudinal pull and resistance to bending when supported at one end. Salviati notes that a rod can withstand a significantly larger force when pulled lengthwise compared to when it is subjected to a bending force. He highlights that the second type of resistance is the focus of their investigation, seeking to understand its proportionality in prisms and cylinders of varying dimensions.

- Mathematical Relationships in Strength: The dialogue delves into the mathematical relationships governing the strength of cylinders and prisms. Several propositions are presented relating the resistance to fracture (bending strength) to the dimensions of the object.

- “The resistance [strength] of a cylinder whose length remains constant varies as the third power of its diameter.”

- “The resistance [strength] of a prism or cylinder of constant length varies in the sesquialteral ratio of its volume.”

- “Prisms and cylinders which differ in both length and thickness offer resistances to fracture [i. e., can support at their ends loads] which are directly proportional to the cubes of the diameters of their bases and inversely proportional to their lengths.”

- Largest Possible Size: The discussion addresses the concept of a maximum size for a prism or cylinder that can support its own weight. It is argued that for any given material and proportion, there exists a specific size that represents the boundary between breaking and not breaking under its own weight. “For there must be a prism of a certain size — in my opinion, it is unique and of a definite size — among all prisms — infinite in number — in occupying that boundary line between breaking and not breaking; so that every larger one will break under its own weight, and every smaller one will not break, but will be able to withstand some force in addition to its own weight.”

- Hollow Solids: The benefit of hollow solids in construction and nature is discussed. It is noted that hollow structures, like the bones of birds or reeds, offer increased strength without proportional increases in weight. This design principle is recognized as being widely employed in both art and nature.

II. The Nature of Matter and Vacuums

The concept of a vacuum and its resistance to separation is explored, along with related ideas about the composition of matter.

- Resistance of the Vacuum: The resistance to the separation of parts in a continuous substance, particularly water, is attributed to the resistance of the vacuum. An experiment is described to measure this force: a cylinder filled with water and a perfectly fitting stopper is inverted, and a weight is attached to the stopper. The weight required to separate the stopper from the water, breaking the continuous column, is presented as a measure of “the force of the vacuum [forza del vacuo].”

- Limitations of Pumps: The observed limitation of pumps to raise water beyond a certain height (eighteen cubits) is linked to the resistance of the vacuum. This fixed elevation is seen as a constant value, independent of the pump’s size. “That is precisely the way it works; this fixed elevation of eighteen cubits is true for any quantity of water whatever, be the pump large or small or even as fine as a straw.”

- Vacuum and Material Strength: The concept of the vacuum’s resistance is then applied to the breaking strength of solid materials. The resistance of a material is considered to have components, one of which is related to the vacuum. A method is outlined to determine the portion of a material’s breaking strength that is attributable to the vacuum resistance by comparing it to the weight of a column of water of the same diameter and eighteen cubits in length.

- Microscopic Vacuums: The dialogue speculates on the possibility of extremely minute vacuums existing within the smallest particles of matter, contributing to the binding force between them. This idea is presented as a “passing thought, still immature and calling for more careful consideration.”

- Infinite Number of Vacuums: The discussion touches on the philosophical paradox of whether an infinite number of vacuums can exist within a finite extent of metal, linking it to the concept of resolving a continuous quantity into infinitely many indivisible points.

III. Motion and Velocity

The excerpts explore various aspects of motion, including falling bodies, motion through different media, and the composition of velocities.

- Motion in a Vacuum: The controversial idea that in a vacuum, bodies of different weights would fall with the same velocity is introduced, challenging the Aristotelian view. Salviati expresses confidence in this despite Simplicio’s disbelief: “I shall never believe that even in a vacuum, if motion in such a place were possible, a lock of wool and a bit of lead can fall with the same velocity.” Salviati assures Simplicio that he has a proper solution.

- Resistance of the Medium: The resistance of the medium through which a body moves is acknowledged as a factor affecting its speed. This resistance is related to the density of the medium. The discussion proposes a method for determining the ratio of speeds of a body in different fluid media by considering the difference between the body’s specific gravity and that of the medium.

- Weight of Air: The question of whether air has weight and how to measure its specific gravity is addressed. An experiment is described involving compressing air into a flask, weighing it, releasing the air, and weighing it again. The weight of the escaped air is then compared to the weight of a volume of water equal to the volume of the escaped air. This experiment is said to show that water is much heavier than air, contrary to some opinions.

- Terminal Speed: The concept of a terminal speed is discussed, where the resistance of the medium eventually checks the acceleration of a falling body and reduces its motion to uniformity, even for very large or dense objects. “I can assert without hesitation that there is no sphere so large, or composed of material so dense but that the resistance of the medium, although very slight, would check its acceleration and would, in time reduce its motion to uniformity.”

- Uniformly Accelerated Motion: The concept of uniformly accelerated motion is a key theme. The distance traversed by a freely falling body is stated to vary as the square of the time. This principle is fundamental to the analysis of projectile motion.

- Composition of Velocities: The combination of horizontal and vertical motions is analyzed, particularly in the context of projectile motion. The concept of compounding two uniform momenta (velocities), one vertical and one horizontal, is presented. The magnitude of the resulting momentum is found by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of the individual momenta. This is presented as a “fixed and certain rule.” This principle is related to the parabolic trajectory of projectiles.

IV. Sound and Music

The nature of sound, its transmission, and the physical basis of musical harmony are explored.

- Sound as Undulations: Sound is described as being produced by the vibrations of a sonorous body, which create undulations that spread through the air and stimulate the ear drum. The experiment with a vibrating glass causing ripples in water is used to illustrate these waves.

- Musical Intervals and Ratios: The physical basis for musical intervals, such as the octave and the fifth, is discussed in terms of ratios of string lengths, tension, and size. The traditional explanation of intervals based on string lengths is presented (octave as 2:1, fifth as 3:2). However, it is noted that achieving the same intervals by changing tension or size requires squaring these ratios. For example, the fifth requires a tension ratio of (3/2)^2 = 9/4.

- Synchronization of Pulses: The physical phenomenon of musical harmony is linked to the simultaneous arrival of pulses from vibrating sources at the ear drum. Consonant intervals like the octave and the fifth are explained by the regular synchronization of these pulses. The octave (2:1 ratio) results in every alternate pulse from one source coinciding with a pulse from the other. The fifth (3:2 ratio) involves a more complex pattern where pulses coincide less frequently, with solitary pulses interspersed between simultaneous ones.

- Displaced Beats: The characteristic of the fifth is described by its “displaced beats” and the specific pattern of solitary pulses occurring between simultaneous pulses. This pattern is related to the tactile sensation experienced by the ear drum, described as a mix of “a gentle kiss and of a bite.”

V. Other Scientific and Philosophical Concepts

Beyond the main themes, the excerpts touch upon other related scientific and philosophical ideas.

- Indivisibles: The philosophical concept of indivisible points and their role in forming continuous quantities is debated. The idea that a line can be composed of an infinite number of indivisible points is explored, leading to paradoxes related to the comparison of discrete and continuous quantities.

- Potential vs. Actual Infinity: The distinction between potentially infinite and actually finite quantities is discussed in the context of dividing a continuous line.

- Levers and Moments: The principle of levers and the concept of “moment” (referring to force or compound force) are introduced in the context of calculating the forces involved in lifting a heavy stone with a lever.

- Equilibrium: The ability of fish to maintain equilibrium in water through the use of a bladder is described as an example of natural engineering that surpasses human capabilities in some operations.

- Projectile Motion and Parabolic Trajectory: The trajectory of projectiles is analyzed, and it is mathematically demonstrated that this trajectory follows a parabolic path. The relationship between the horizontal and vertical components of motion is explored, and tables are provided showing the altitudes and sublimities of parabolas for different angles of elevation and initial speeds.

- Perpetual Motion: The concept of a body maintaining acquired velocity is discussed, although the context of falling bodies and inclined planes indicates a focus on understanding the forces and motions involved rather than advocating for perpetual motion in the strict sense.

- Measure of Momentum and Speed: Momentum and speed are treated as quantifiable concepts that can be measured and compared. Different scales and units are implicitly or explicitly used in the discussions and calculations.

This briefing document provides a comprehensive overview of the main themes and important ideas present in the provided excerpts, highlighting key quotes and concepts discussed by the characters.

Natural Science Explorations

What are the limitations on the strength of materials based on their size?

The sources indicate that the strength of a material does not scale directly with its size. A rod that is just strong enough to support its own weight will break if its length is increased by even a hair’s breadth. Furthermore, larger structures made of the same material with the same proportions as smaller ones will not be able to support a proportionally equal load. This is because the resistance to breaking changes based on the dimensions of the object, and this resistance is overcome by the increasing weight or force acting upon it as size increases.

How is the force of a vacuum explained and measured?

The force of a vacuum is described as the resistance to the separation of the parts of a continuous substance when there is no other resistance present. An experiment is proposed using a hollow cylinder (preferably of glass) with a tightly fitting stopper. The space between the stopper and the upper end of the cylinder is filled with water, and then the vessel is inverted. By attaching weights to the stopper until it separates from the water, the force of the vacuum can be measured. This resistance is likened to a rope being stretched until it breaks.

How is the phenomenon of a column of water reaching a fixed maximum height in a pump explained?

The sources attribute the fixed elevation of eighteen cubits that water reaches in a pump to the resistance of the vacuum. When the water is pulled up, it is stretched, and like a rope, it will break when its weight exceeds a certain limit. This maximum length is consistent regardless of the pump’s size or the amount of water, and the weight of the water column at this height represents the value of the vacuum’s resistance for that specific diameter. This concept allows for the determination of the maximum length various solid materials can be elongated without breaking under their own weight by comparing their breaking strength to the weight of a water column of equivalent diameter and 18 cubits in height.

What is the discussion regarding the potential infinity of points within a finite extent?

The sources delve into the paradox of potentially having an infinite number of indivisible points within a finite line or magnitude. This is explored through thought experiments involving the division of a line into increasingly smaller parts, suggesting that the ultimate division could result in an infinite number of indivisible components. The analogy of forming polygons with an increasing number of sides that eventually approximate a circle is used to suggest that a circle, as a polygon with an infinite number of sides, can be considered to have an infinite number of points. This challenges the idea that parts only exist actually after division, proposing that an infinite number of parts can exist potentially within a finite entity and be brought into actuality through transformation (like bending a line into a circle).

How is sound and musical harmony related to wave phenomena?

The sources connect sound to the vibration of bodies and the resulting propagation of waves through a medium, like air or water, which are then perceived by the ear. Experiments with vibrating strings and glasses of water are described, illustrating the creation of regular waves. Musical intervals are explained in terms of ratios, but the deeper understanding is found in the frequency of vibrations and the interaction of waves. For example, the octave corresponds to a 2:1 ratio in length but a 4:1 ratio in tension or size of a string. The fifth is linked to a 3:2 ratio in length, but a 9:4 ratio in tension or size. Harmonious sounds are associated with wave pulses that strike the ear drum simultaneously at regular intervals, while less consonant intervals, like the fifth, involve more complex and offset pulse patterns that create a different sensation.

What is the relationship between the strength of solid figures (prisms and cylinders) and their dimensions?

The sources analyze the resistance of prisms and cylinders to fracture and bending. It’s shown that the bending strength of a prism or cylinder with a constant length varies as the cube of its diameter. When considering figures that differ in both length and thickness, their resistance to fracture is directly proportional to the cube of their diameter and inversely proportional to their length. A key finding is that if the length and thickness increase in the same proportion, their strength does not remain constant; larger similar figures are weaker relative to their size and will break under their own weight while smaller ones can withstand additional force. There exists a maximum size for a similar figure that can just support its own weight.

How does resistance of the medium affect the motion of falling bodies?

The sources acknowledge that the resistance of the medium (like air or water) affects the motion of falling bodies. While a body’s acquired velocity tends to be maintained, the medium’s resistance acts as a cause of retardation, particularly at higher velocities. The density of the medium plays a role, with denser media causing greater resistance. The sources explore how to quantify this resistance and its effect on speed, noting that differences in speed are more pronounced for bodies of different substances moving through the same medium or for the same body moving through different media. The specific gravity of air is also discussed and experimentally determined relative to water to further understand its effect on motion.

How are projectile trajectories analyzed, and what quantities are used to describe their motion?

The sources demonstrate that the trajectory of a projectile can be described as a parabola. This motion is understood as a compound of a uniform horizontal velocity and a naturally accelerated vertical velocity (due to gravity). Quantities like space, time, and momentum are employed to analyze this motion. The vertical distance fallen is proportional to the square of the time, while the horizontal distance is proportional to the uniform horizontal speed and the time. The momentum acquired at a certain point is related to the time of fall and the initial velocity. The analysis also involves concepts of “altitude” and “sublimity” of the parabola, relating them to the initial speed and angle of projection to determine the amplitude and height of the trajectory. Tables are provided to relate angles of elevation to the altitudes and sublimities of parabolas for given initial speeds or amplitudes.

The Original Text

TWO NEW SCIENCES BY GALILEO

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY KEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALLAS

ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., LIMITED LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO

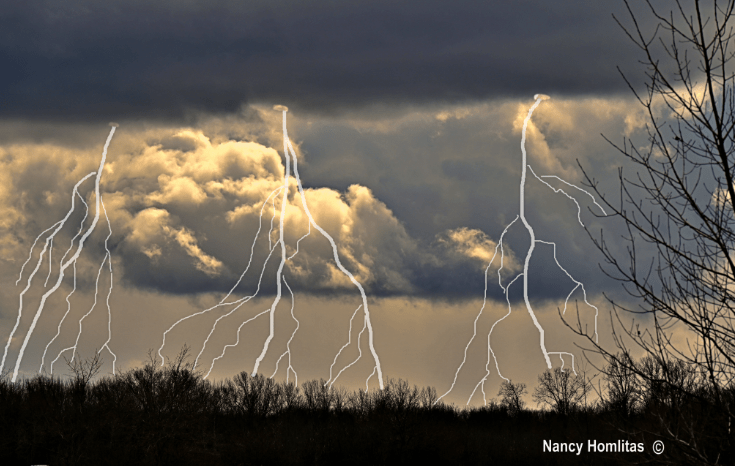

GALILEO GALILEI.

Subterman’s portrait, painted about 1640; now in the Galleria di Pitti at Florence.

DIALOGUES

CONCERNINC

TWO NEW SCIENCES

BY

GALILEO GALILEI

Translated from the Italian and Latin into English by

HENRY CREW AND ALFONSO DE SALVIO

of Northwestern University

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

ANTONIO FAVARO

of the University of Padua.

” I think with vour friend that it has been of late too much the mode to slight the learning of the ancients.” Benjamin Franklin, Phil. Trans.

6* 445- (I774-)

Nrro f nrb

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1914

All rights reserved

02>

COPYRIGHT, 1914

BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped. Published May, 1

“La Dynamique est la science des forces accelera- trices or retardatrices, et des mouyemens varies qu’elles doivent produire. Cette science est due entierement aux modernes, et Galilee est celui qui en a jete les premiers fondemens.” Lagrange Mec. Anal. I. 221.

TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE

OR more than a century English speaking students have been placed in the anomalous position of hearing Galileo constantly re- ferred to as the founder of modern physical

science, without having any chance to read, in their own language, what Galileo himself has to say. Archimedes has been made available by Heath ;Huygens’ Lighthas been turned into English by Thompson, while Motte has put the Principia of Newton back into the language in which it was conceived. To render the Physics of Galileo also accessible to English and American students is the purpose of the following translation.

The last of the great creators of the Renaissance was not a prophet without honor in his own time; for it was only one group of his country-men that failed to appreciate him. Even during his life time, his Mechanics had been rendered into French by one of the leading physicists of the world, Mersenne.

Within twenty-five years after the death of Galileo, his Dia- logues on Astronomy, and those on Two New Sciences, had been

done into English by Thomas Salusbury and were worthily printed in two handsome quarto volumes. The Two New Sciences, which contains practically all that Galileo has to say on the subject of physics, issued from the English press in 1665.

vi TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE It is supposed that most of the copies were destroyed in the great London fire which occurred in the year following. We are not aware of any copy in America : even that belonging to the British Museum is an imperfect one.

Again in 1730 the Two New Sciences was done into English by Thomas Weston; but this book, now nearly two centuries old, is scarce and expensive. Moreover, the literalness with which this translation was made renders many passages either ambiguous or unintelligible to the modern reader. Other than these two, no English version has been made.

Quite recently an eminent Italian scholar, after spending thirty of the best years of his life upon the subject, has brought to completion the great National Edition of the Works of Galileo. We refer to the twenty superb volumes in which Pro-

fessor Antonio Favaro of Padua has given a definitive presenta- tion of the labors of the man who created the modern science of

physics. The following rendition includes neither Le Mechaniche of Galileo nor his paper De Motu Accelerate, since the former of these contains little but the Statics which was current before the time of Galileo, and the latter is essentially included in the Dialogue of the Third Day. Dynamics was the one subject to which under various forms, such as Ballistics, Acoustics, As-

tronomy, he consistently and persistently devoted his whole life. Into the one volume here translated he seems to have gathered, during his last years, practically all that is of value either to the engineer or the physicist. The historian, the philosopher, and the astronomer will find the other volumes replete with interesting material.

It is hardly necessary to add that we have strictly followed the text of the National Edition — essentially the Elzevir edition of 1638. All comments and annotations have been omitted save here and there a foot-note intended to economize the reader’s time. To each of these footnotes has been attached the signa-

ture [Trans.] in order to preserve the original as nearly intact as

possible. Much of the value of any historical document lies in the lan-

guage employed, and this is doubly true when one attempts to

TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE vii trace the rise and growth of any set of concepts such as those employed in modern physics. We have therefore made this translation as literal as is consistent with clearness and modern-

ity. In cases where there is any important deviation from this rule, and in the case of many technical terms where there is no deviation from it, we have given the original Italian or Latin phrase in italics enclosed in square brackets. The intention here is to illustrate the great variety of terms employed by the early physicists to describe a single definite idea, and conversely, to illustrate the numerous senses in which, then as now, a single word is used. For the few explanatory English words which are placed in square brackets without italics, the translators alone are responsible. The paging of the National Edition is indicated in square brackets inserted along the median line of the page. The imperfections of the following pages would have been

many more but for the aid of three of our colleagues. Professor D. R. Curtiss was kind enough to assist in the translation of those pages which discuss the nature of Infinity: Professor O. H. Basquin gave valuable help in the rendition of the chapter on Strength of Materials; and Professor O. F. Long cleared up the meaning of a number of Latin phrases.

To Professor A. Favaro of the University of Padua the trans- lators share, with every reader, a feeling of sincere obligation

for his Introduction. H. C.

A. DE S.

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS, 15 February, 1914.

INTRODUCTION

RITING to his faithful friend Elia Diodati,

Galileo speaks of the “New Sciences ” which he had in mind to print as being “superior to everything else of mine hitherto pub-

lished”; elsewhere he says “they contain results which I consider the most important

of all my studies”; and this opinion which he expressed concerning his own work has

been confirmed by posterity: the “New Sciences” are, indeed, the masterpiece of Galileo who at the time when he made the above remarks had spent upon them more than thirty laborious years.

One who wishes to trace the history of this remarkable work will find that the great philosopher laid its foundations during

the eighteen best years of his life — those which he spent at Padua. As we learn from his last scholar, Vincenzio Vivian i, the numerous results at which Galileo had arrived while in this

city, awakened intense admiration in the friends who had wit- nessed various experiments by means of which he was accus-

tomed to investigate interesting questions in physics. Fra Paolo Sarpi exclaimed: To give us the Science of Motion, God and Nature have joined hands and created the intellect of Galileo.

And when the “New Sciences” came from the press one of his foremost pupils, Paolo Aproino, wrote that the volume contained

much which he had “already heard from his own lips” during student days at Padua.

Limiting ourselves to only the more important documents which might be cited in support of our statement, it will suffice to mention the letter, written to Guidobaldo del Monte on the 29th of November, 1602, concerning the descent of heavy bodies

x INTRODUCTION

along the arcs of circles and the chords subtended by them; that to Sarpi, dated i6th of October, 1604, dealing with the free fall

of heavy bodies; the letter to Antonio de’ Medici on the nth

of February, 1609, in which he states that he has “completed all the theorems and demonstrations pertaining to forces and re-

sistances of beams of various lengths, thicknesses and shapes, proving that they are weaker at the middle than near the ends, that they can carry a greater load when that load is distributed throughout the length of the beam than when concentrated at one point, demonstrating also what shape should be given to a beam in order that it may have the same bending strength at

every point,” and that he was now engaged “upon some ques- tions dealing with the motion of projectiles”; and finally in the

letter to Belisario Vinta, dated 7th of May, 1610, concerning his return from Padua to Florence, he enumerates various pieces of work which were still to be completed, mentioning explicitly three books on an entirely new science dealing with the theory of motion. Although at various times after the return to his native state he devoted considerable thought to the work which, even at that date, he had in mind as is shown by certain frag-

ments which clearly belong to different periods of his life and which have, for the first time, been published in the National Edition; and although these studies were always uppermost in his thought it does not appear that he gave himself seriously to them until after the publication of the Dialogue and the com-

pletion of that trial which was rightly described as the disgrace of the century. In fact as late as October, 1630, he barely men-

tions to Aggiunti his discoveries in the theory of motion, and only two years later, in a letter to Marsili concerning the motion of projectiles, he hints at a book nearly ready for publication in which he will treat also of this subject; and only a year after this he writes to Arrighetti that he has in hand a treatise on the resistance of solids.

But the work was given definite form by Galileo during his enforced residence at Siena: in these five months spent quietly with the Archbishop he himself writes that he has completed

“a treatise on a new branch of mechanics full of interesting and useful ideas”; so that a few months later he was able to send

INTRODUCTION xi

word to Micanzio that the “work was ready”; as soon as his friends learned of this, they urged its publication. It was, how-

ever, no easy matter to print the work of a man already con- demned by the Holy Office: and since Galileo could not hope to

print it either in Florence or in Rome, he turned to the faithful Micanzio asking him to find out whether this would be possible in Venice, from whence he had received offers to print the Dia-

logue on the Principal Systems, as soon as the news had reached there that he was encountering difficulties. At first everything went smoothly; so that Galileo commenced sending to Micanzio some of the manuscript which was received by the latter with an enthusiasm in which he was second to none of the warmest admirers of the great philosopher. But when Micanzio con-

sulted the Inquisitor, he received the answer that there was an express order prohibiting the printing or reprinting of any work of Galileo, either in Venice or in any other place, nullo excepto.

As soon as Galileo received this discouraging news he began to look with more favor upon offers which had come to him from Germany where his friend, and perhaps also his scholar, Gio-

vanni Battista Pieroni, was in the service of the Emperor, as military engineer; consequently Galileo gave to Prince Mattia

de’ Medici who was just leaving for Germany the first two Dia- logues to be handed to Pieroni who was undecided whether to

publish them at Vienna or Prague or at some place in Moravia; in the meantime, however, he had obtained permission to print both at Vienna and at Olmiitz. But Galileo recognized danger at every point within reach of the long arm of the Court of Rome; hence, availing himself of the opportunity offered by the arrival of Louis Elzevir in Italy in 1636, also of the friendship between the latter and Micanzio, not to mention a visit at Arcetri, he decided to abandon all other plans and entrust to the Dutch publisher the printing of his new work the manu-

script of which, although not complete, Elzevir took with him on his return home.

In the course of the year 1637, the printing was finished, and at the beginning of the following year there was lacking only the index, the title-page and the dedication. This last had,

xii INTRODUCTION

through the good offices of Diodati, been offered to the Count of Noailles, a former scholar of Galileo at Padua, and since 1634 ambassador of France at Rome, a man who did much to alleviate the distressing consequences of the celebrated trial; and the offer was gratefully accepted. The phrasing of the dedication deserves brief comment. Since Galileo was aware, on the one hand, of the prohibition against the printing of his works and since, on the other hand, he did not wish to irritate the Court of Rome from whose hands he was always hoping for complete freedom, he pretends in the dedicatory letter (where, probably through excess of caution, he gives only main outlines) that he had nothing to do with the printing of his book, asserting that he will never again publish any of his researches, and will at most distribute here and there a manuscript copy. He even expresses great surprise that his new Dialogues have fallen into the hands of the Elzevirs and were soon to be published; so that, having been asked to write a dedication, he could think of no man more worthy who could also on this occasion defend him against his enemies. As to the title which reads: Discourses and Mathematical

Demonstrations concerning Two New Sciences pertaining to Me- chanics and Local Motions, this only is known, namely, that the title is not the one which Galileo had devised and suggested; in fact he protested against the publishers taking the liberty of

changing it and substituting “a low and common title for the noble and dignified one carried upon the title-page.”

In reprinting this work in the National Edition, I have fol- lowed the Leyden text of 1638 faithfully but not slavishly, be- cause I wished to utilize the large amount of manuscript ma- terial which has come down to us, for the purpose of correcting

a considerable number of errors in this first edition, and also for the sake of inserting certain additions desired by the author himself. In the Leyden Edition, the four Dialogues are followed

by an “Appendix containing some theorems and their proofs, deal- ing with centers of gravity of solid bodies, written by the same

Author at an earlier date” which has no immediate connection with the subjects treated in the Dialogues; these theorems were

found by Galileo, as he tells us, “at the age of twenty-two and

INTRODUCTION xiii

after two years study of geometry” and were here inserted only to save them from oblivion.

But it was not the intention of Galileo that the Dialogues on the New Sciences should contain only the four Days and the above-mentioned appendix which constitute the Leyden Edi-

tion; while, on the one hand, the Elzevirs were hastening the printing and striving to complete it at the earliest possible date, Galileo, on the other hand, kept on speaking of another Day, besides the four, thus embarrassing and perplexing the printers. From the correspondence which went on between author and publisher, it appears that this Fifth Day was to have treated

“of the force of percussion and the use of the catenary”; but as the typographical work approached completion, the printer became anxious for the book to issue from the press without further delay; and thus it came to pass that the Discorsi e Dimostrazioni appeared containing only the four Days and the Appendix, in spite of the fact that in April, 1638, Galileo had

plunged more deeply than ever “into the profound question of percussion” and “had almost reached a complete solution.” The “New Sciences” now appear in an edition following the

text which I, after the most careful and devoted study, deter- mined upon for the National Edition. It appears also in that

language in which, above all others, I have desired to see it. In this translation, the last and ripest work of the great philosopher makes its first appearance in the New World: if toward this important result I may hope to have contributed in some meas-

ure I shall feel amply rewarded for having given to this field of research the best years of my life.

ANTONIO FAVARO. UNIVERSITY OF PADUA,

2yth of October, 1913.

D I SC O R S I

DIMOSTRAZIONI

MATEMATICHE,

in tor no a due nttoue {cien^c

Atcenenci alia MECANICX & i MOVIMENTI LOCALI,

dclSignor

GALILEO GALILEI LINCEO, Filofofo e Matematico primario del Sercniflimo

Grand Duca di Tofcana.

IN L E I D A,