The provided text is an excerpt from a book detailing the history of Bangladesh. It covers a vast timespan, from prehistory to the early 21st century, exploring diverse themes such as the country’s geography, agricultural practices, political systems, cultural development, and the impact of colonialism and globalization. The text is richly illustrated with images and maps, and frequently cites scholarly sources to support its historical narrative. Specific chapters examine key events like the Partition of India and the Bangladesh Liberation War.

A History of Bangladesh: Study Guide

Short Answer Quiz

- Describe the geographical features of Bangladesh and how they shape the region’s environment.

- What is a “shishu” and what factors endanger its survival?

- How did various language families contribute to the development of the Bengali language?

- Discuss the mobility of urban centers and states in the Bengal delta.

- What was the Mughal system of governance like in Bengal?

- How did the colonial period impact land ownership and class structures in the Bengal delta?

- What was the Language Movement, and what was its significance?

- How did the idea of “Bangladeshiness” develop as distinct from “Bengaliness?”

- What is the Grameen Bank and how does it contribute to development in Bangladesh?

- Briefly explain how the culture of Bangladesh can be described as both diverse and food-centered.

Answer Key

- Bangladesh is a vast flood plain formed by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, which deposit silt and create a landscape of rivers, marshes, and lakes. The region is prone to monsoonal flooding, cyclones, and saltwater intrusion, which significantly shapes human life.

- A shishu is a freshwater dolphin indigenous to the Ganges and Brahmaputra river systems. It is endangered by dams, habitat degradation, water pollution, and entanglement in fishing nets.

- The Bengali language has roots in Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic, and Dravidian languages, as well as Indo-European languages which began to spread around the 4th century BCE. Words related to nature, agriculture and settlement often derive from the earlier languages.

- Due to the ever-changing river courses, urban centers and states in the Bengal delta were notably mobile. Towns often declined when nearby rivers shifted, and political organizations were similarly prone to rising and falling.

- The Mughal government imposed a layer of centralized authority over existing local control, with local lords (zamindars) often remaining semi-independent. They divided the region into provinces, regions, subdivisions, and revenue villages for taxation and administration.

- The colonial period saw a rise in Hindu zamindars, especially in the eastern delta, while Muslim cultivators dominated in the same area. Land ownership became increasingly stratified, with many benefiting from the colonial state’s patronage.

- The Language Movement was a political movement in East Pakistan advocating for the recognition of Bengali as an official language of Pakistan. It grew from protests in 1952 into an assertion of Bengali identity and a major force in the independence of Bangladesh.

- “Bengaliness” emphasized a linguistic and cultural heritage, representing an idealized rural homeland. “Bangladeshiness” was a new concept developed under military rule, creating an idea of a national identity separate from West Pakistan’s influence.

- The Grameen Bank is a microfinance institution that provides small loans to impoverished people, primarily women, to help them start businesses and improve their economic standing, emphasizing local initiatives for development.

- Bangladesh has a deeply food-centric culture with a diverse array of dishes, influenced by regional, community, class, and family variations. Rice and fish are staple foods, with a variety of other crops, spices, and sweets playing a prominent role.

Essay Questions

- Analyze the interplay of environmental factors and human societies in shaping the history of Bangladesh, focusing on the delta’s unique geography and its impacts on settlement patterns, agriculture, and economic development.

- Discuss the evolution of political identities in Bangladesh, focusing on the influence of historical events, religious factors, and nationalist movements on shaping concepts of “Bengali” and “Bangladeshi” identity.

- Assess the impact of colonial rule on the socio-economic and political structures of the Bengal delta, considering both the immediate and long-term consequences of British administration and economic policies.

- Examine the causes and consequences of major conflicts within Bangladesh including the Language Movement, the Liberation War, and the Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict and consider how these conflicts have influenced the region’s political landscape and national identity.

- Evaluate the challenges and opportunities that Bangladesh has faced since its independence, including socio-economic development, environmental sustainability, and the formation of a national culture, while also considering its transnational linkages.

Glossary of Key Terms

Ajlaf: Low-born. Alpona: Floor decoration. Āman: Autumn rice. Ashraf: Aristocratic. Atrap: Low-born. Āuś: Spring rice. Baul: A devotional community. Bhadralok: Gentlefolk. Bhat: Cooked rice. Bigha: 0.14 hectare. Bil: Low land, lake. Birongona: (War) heroine. Bisho Ijtema: World gathering. Bongobondhu: Friend of Bengal. Boro: Winter rice. Burka: Tent-like garment. Chacha: Uncle. Chaul: Husked rice. Danga: High land. Dāoyāt: Invitation. Dhān: Unhusked rice. Dhenki: Rice husker. Didi: Elder sister. Doba: Waterhole. Doi: Sweet yogurt. Ekushe: 21 (February), referring to the date of the Language Movement protests. Firingi: Europeans, referring specifically to the Portuguese. Ghat: Landing place. Gherao: Surrounding. Gramin: Rural. Hāl: Plough. Haor: Low land, lake. Hijra: Migration. Hortal: General strike. Hundi: Banking system. Ilish: Hilsa (a fish). Jal: Fishing net. Jam: Blackberry. Jatiyo Shongshod: Parliament. Jatir Jonok: Father of the Nation. Jātrā: Village opera. Jhum: Hill agriculture. Jihadi: Islamic warrior. Jilapi: A sweet. Joy Bangla! Victory to Bengal! Kacha: Mud-made. Kanthal: Jackfruit. Kheshari: Grass pea. Khichuri: Rice-lentil mix. Khola: Open land. Kul: Sour plum. Krishok: Peasant. Langol: Plough. Lojja: Shame. Loshkor: Sailor. Lungi: Men’s sarong. Madrasha: Islamic school. Mastan: Rowdy, gangster. Maulana: Muslim scholar. Milad: Thanksgiving. Mishti: Sweet. Mofussil: Countryside. Monga: Near-famine. Mouza: Revenue village. Muhajir: Immigrant. Mujibbad: Mujibism. Mukti Bahini: Freedom fighters. Mukti Joddha: Freedom fighter. Nobab: Nawab, ruler. Olandaz: Dutch; pirate. Panta Bhat: Soaked rice. Para: Hamlet. Payesh: Sweet dish. Pir: Spiritual guide. Pohela Boishakh: Bengali New Year. Porgona: Subdivision. Porota: Flatbread. Potti: Village. Pottonidari: Sub-infeudation. Pukur: Pond. Ra’iyat: Tenant. Rastrobhasha: National language. Razbari: Palace. Rokkhi Bahini: Security Force. Roshkodom: A sweet. Roshmalai: A sweet. Roshogolla: A sweet. Ruti: Flatbread. Shanti Bahini: Peace Force. Shankari: Conch-shell-maker. Shari: Saree. Shemai: A sweet dish. Shishu: 1) river dolphin, 2) child. Shobha: Association. Shodeshi: Own-country. Shohid Minar: Martyrs’ memorial. Shomaz: Congregation. Shonar Bangla: Golden Bengal. Shondesh: A sweet. Shorkar: Government. Shuba: Province. Shuntki Machh: Dried fish. Taka: Bangladesh currency. Tebhaga: Three shares. Tezpata: Cassia leaf. Thana: Police station. Torkari: Side dish. Tupi: Cap. Zamindar: Landlord/tax collector. Zindabad! Long live!

A History of Bangladesh: Delta, Identity, and Nation

Okay, here is a detailed briefing document based on the provided excerpts from “A History of Bangladesh” by Willem van Schendel:

Briefing Document: A History of Bangladesh

Introduction:

This document provides a detailed overview of the key themes, ideas, and facts presented in the provided excerpts from Willem van Schendel’s “A History of Bangladesh.” The excerpts emphasize the long and complex history of the region, exploring the interplay of geographical forces, socio-political developments, and cultural evolution that have shaped modern Bangladesh. The document highlights the distinct regional identity, the impact of foreign rule, and the constant negotiation of various identities within this densely populated area.

Key Themes and Ideas:

- Geographical Determinism and the Bengal Delta:

- Dynamic Landscape: The book begins by emphasizing the profound influence of the Bengal delta’s unique geography on its society. The delta is described as “an immense floodplain stretching between the mountains and the sea,” formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers.

- Water as a Shaping Force: The interplay of river systems, monsoon rains, and seawater creates a dynamic and often challenging environment. Flooding is a recurring phenomenon, with “About 20 percent of the country is inundated every summer.” The landscape is constantly being reshaped by the movement of rivers and the deposition of silt.

- Quote: “In summer, however, nature is out of control and Bangladesh turns into an amphibious land. Rivers widen, rains pour down and storms at sea may hamper the discharge of all this water. The result is flooding.”

- Adaptability: This constant flux has led to flexible and transient settlement patterns, where villages are “not clustered around a central square, protected by defensive walls or united in the maintenance of joint irrigation works. Instead they consist of scattered homesteads and small hamlets.”

- Unstable Geology: The text describes the area as being prone to earthquakes, caused by the collision of tectonic plates, and featuring geological features such as terraces and depressions.

- Quote: “The unstable geological structures underlying Bangladesh generate frequent earthquakes, most of them light but some strong enough to cause widespread destruction.”

- The Development of Regional Identity:

- Early Regional Distinction: The delta developed “a very distinct regional identity quite early on.” This identity was shaped by its environment and its position as a crossroads for various cultures and languages.

- Multiple Frontiers: The region’s history is characterized by multiple frontiers: between land and water, between states and other forms of rule, and between different cultural influences.

- Linguistic Diversity: While Bengali is now dominant, the area was initially home to speakers of Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic, and Dravidian languages.

- Cultural Fusion: Over time, a “recognisable regional culture” emerged, largely centered around a hyphenated identity of being both Muslim and Bengali.

- Quote: “…a crucial hyphenation of Bengali and Muslim did occur, shaping the way most inhabitants of the active delta understood themselves and their society.” However the book also notes that, “even today, there are many people in Bangladesh who subscribe to only one of the two identities or to neither.”

- Trade and Transnational Linkages:

- Strategic Location: The Bengal delta was a major crossroads for trade routes, both land and sea-based. Early urban centers were established along major rivers, acting as emporiums for goods traveling between China and Alexandria.

- Quote: “The location of the Bengal delta allowed its urban centres to become important crossroads for trade.”

- Maritime Activity: Seaborne trade was a key feature of the region, as early coins depict boats. The inhabitants were active participants in long-distance trade and maritime warfare.

- European Contact: European traders, such as the Portuguese, Dutch, and English, became increasingly influential, though their relationships with local traders varied from cooperation to conflict. The European presence resulted in the importation of “precious metals – gold from Japan, Sumatra and Timor, silver from Japan, Burma and Persia and silver coins from Mexico and Spain – but also copper, tin and a variety of spices such as pepper, cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon.”

- Quote: “The impact of European activities in the Bengal delta was not merely economic and political. When sailors from a shipwrecked Dutch vessel were washed ashore in Noakhali (eastern Bangladesh) in 1661, they found that fishermen and villagers spoke to them in Portuguese.”

- Political Evolution and the Rise and Fall of States:

- Fluid Political Landscape: The region saw the continual emergence and decline of local and regional polities, occasionally integrated into larger realms like the Maurya and Gupta empires.

- Quote: “The early history of state formation in the Bengal delta can be described as a continual emergence and decline of local and regional polities that only occasionally became integrated into large realms.”

- Mughal Rule: The Mughal conquest in the 16th-18th centuries brought a layer of centralized authority, though local lords, or “zamindars,” often remained semi-independent. Mughal rule also brought some cultural shifts with the imposition of new administrative and revenue systems, whose legacies persist to the present day.

- Quote: “The Mughal conquest brought Bengal devastation and brutality.”

- British Colonialism: The British East India Company gradually took control of the region, which became a major source of agrarian exports like jute. This led to the enrichment of the zamindari gentry, which changed in composition as “the colonial period saw an advance of Hindu landlords.” This eventually led to the merging of “religious and class identities, with Hindu zamindars at the apex of a local society consisting largely of Muslim cultivators.” The regional difference between the eastern and western delta would eventually become a “highly salient political question towards its end.”

- Post-Colonial State: The book highlights the difficulties in establishing a stable political system after independence from Pakistan in 1971, which saw several military coups and the rise of Islamist politics. The text emphasizes the struggle between “Bengaliness” and “Bangladeshiness.”

- Quote: “The officers who seized state power in the Bengal delta after 1975 had built their careers during Pakistan’s military dictatorships (1958–71). Disdainful of civilian politics, they saw themselves as more capable and deserving of running the state than politicians.”

- Regional Tensions: The issue of regional autonomy, particularly in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, has remained a persistent challenge.

- Quote: “The third persistent legacy from the period of military rule – in addition to the struggle between ‘Bengaliness’ and ‘Bangladeshiness’ and the rise of Islamist politics – is an inability to accommodate regional autonomy.”

- Culture and Identity in Independent Bangladesh:

- Nation-Building: After 1971, the focus shifted towards nation-building and establishing a distinct Bangladeshi identity. The core pillars of this identity are language, a regional style, and a search for modernity.

- Quote: “Independence brought cultural autonomy to the delta and a new project of nation-building. Now its inhabitants were invited to imagine themselves as Bangladeshis.”

- Cultural Debates: There are continuous debates about what it means to be Bangladeshi, as new cultural influences intersect with older traditions and the legacy of military rule. The text notes that “…for a growing number the national context is not the only one. Whether they live in Bangladesh or have fanned out across the globe, they are in touch with transnational cultural visions that vary from secular to orthodox, from radical to moderate and from conservative to avant-garde.”

- Quote: “Being a Bangladeshi today means consciously making cultural choices all the time. Yet a multilayered culture has always been the hallmark of the Bengal delta. The delta’s history of multiple, moving frontiers has simply entered a new and exciting phase.”

- Food as Culture: Food plays a crucial role in Bangladeshi culture, with rice and fish as staples. However, many people can only rarely afford these items, subsisting more on lentils and vegetable dishes, and the cuisine itself varies widely by region and social group.

- Quote: “As they say in the region, ‘fish and rice make a Bengali’ (māche bhāte bāṅgālı̄), and this is true, at least for those who can afford to eat well.”

Important Facts and Figures:

- Population Density: Bangladesh is the seventh most populous country on earth, with a population greater than that of Russia or Japan.

- Flooding: About 20 percent of the country is inundated every summer.

- Silt Deposition: Over a billion metric tons of silt are delivered to the Indian Ocean annually.

- Rainfall: Cherrapunji, just across the border in India, receives an annual rainfall of 11 meters.

- River Systems: Bangladesh is crisscrossed by multiple rivers, including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna.

- Trade: The Bengal delta was a major hub for trade routes, connecting Asia with the Middle East and Europe.

- Language: Bengali is the dominant language in the region, although many other languages were spoken earlier, and are still spoken in certain areas of the country today, including Sylheti, Chittagonian, and Chakma.

Conclusion:

The excerpts from “A History of Bangladesh” reveal a land shaped by powerful natural forces and a rich, diverse cultural history. The region’s story is one of constant adaptation, negotiation, and transformation. Bangladesh has always been in a state of flux, with moving rivers, moving borders, and a shifting kaleidoscope of ethnicities and religions. The book concludes that despite the myriad changes in its history, the country still embodies a sense of “multilayered culture” which is in a process of continuous evolution. Understanding this dynamic is essential for comprehending the complexities of modern Bangladesh.

Bangladesh: Geography, History, and Culture

What are the primary geographical features that have shaped Bangladesh?

Bangladesh is primarily a vast flood plain formed by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers and their tributaries. This deltaic region is extremely fertile due to the thick layers of silt deposited by these rivers. The low-lying land is also heavily influenced by monsoon rains and seawater incursions from the Bay of Bengal. These geographical features contribute to regular flooding, with about 20% of the country being inundated each summer, and a landscape defined by a network of rivers, marshes and lakes.

How has the movement of rivers impacted the urban centers and settlement patterns in Bangladesh?

The dynamic nature of the rivers has profoundly affected the development and decline of urban centers in Bangladesh. Cities located along major rivers often thrived as trade ports. However, when a river changed course or a port silted up, these cities would decline. This led to flexible patterns of urbanization where towns and cities were remarkably mobile. Settlements in Bangladesh tend to be scattered homesteads and small hamlets as opposed to concentrated villages, reflecting a landscape where boundaries between land and water are ever-shifting.

What are the main historical language families present in Bangladesh?

While Bengali is the predominant language today, Bangladesh has been a meeting ground for several language families. These include Tibeto-Burman (e.g., Khasi, Garo), Austro-Asiatic (e.g., Santal, Munda), and Dravidian languages (e.g., Kurukh), which were spoken before the spread of Indo-European languages (like Bengali). Words related to land, water, and agriculture in Bengali often derive from these older language families. In some areas of Bangladesh, especially in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and Sylhet, minority languages like Chakma, Chittagonian and Sylheti are spoken that are distinct from standard Bengali.

How did the Mughal Empire’s rule affect Bengal and how did local power structures change?

The Mughal Empire imposed a layer of centralized authority over existing local control systems in Bengal. While the Mughal’s established administrative units like subas (provinces), sarkars (regions) and parganas (subdivisions), the local lords or zamindars still held substantial influence. The Mughal conquest led to devastation and brutality but their land revenue system, however, saw the creation of a landholding aristocracy. Over time, with the decline of the Mughal empire and rise of British colonial rule, the composition of the zamindar class shifted from predominantly Muslim to increasingly Hindu, especially in parts of the eastern delta.

How did the British colonial period change the economic and social landscape of Bengal?

The British colonial period saw the rise of zamindari landowners, who benefitted from the British state’s patronage. The British pushed Bengal to produce agricultural exports like indigo and jute, which resulted in a monetized regional economy. In eastern Bangladesh, peasant smallholders had dwindling land holdings due to population growth and inheritance, and were forced into market production. The regional economy became highly monetised and exposed to international market uncertainties. While some elites in northern and western Bangladesh benefitted from their role as agrarian lenders.

What are the key elements of Bangladeshi national identity?

Bangladeshi national identity is complex, combining various elements. A core aspect is pride in the Bengali language, which fueled the national movement and led to the creation of independent Bangladesh. Another aspect is the “regional style,” which emphasizes aspects of rural life and cultural sensibilities seen in folk songs and mystical traditions. The idea of a “Bangladeshi” identity has been challenged by the rise of Islamist politics, which often emphasizes a Muslim identity over a Bengali one. There are different views on the hyphenated identity of Bengali-Muslim. Other identities like Bengali-Hindu also exist in the population, along with groups who do not consider themselves either Bengali or Muslim like the Chakma and Garo peoples.

What are some of the significant challenges to the development and environmental sustainability of Bangladesh?

Bangladesh faces numerous challenges, including poverty, population density, and environmental vulnerability. The country is highly dependent on its deltaic environment, which makes it susceptible to flooding, cyclones, and climate change impacts. Deforestation, water pollution, and unsustainable land use practices also pose significant threats to its biodiversity. The country has historically depended on foreign assistance for development.

What role does food play in Bangladeshi culture and identity?

Food is central to Bangladeshi culture. Rice is the staple, eaten with spicy side dishes and fish. The saying, “fish and rice make a Bengali,” reflects the importance of these elements in the diet and cultural identity. Bangladeshi cuisine is known for its diverse and intricate dishes that vary by region, community and class. Sweets (mishti) are a very important part of the culture and are given as gifts during visits with family and friends and are an essential part of religious festivals and life events.

A History of Bangladesh

Okay, here is a detailed timeline and cast of characters based on the provided text:

Timeline of Main Events in Bangladesh History

- Prehistory:Geological formation of the Bengal Delta by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, creating a vast floodplain over millennia.

- Emergence of distinct regional identity in the Bengal Delta, characterized by unique environmental challenges and cultural adaptations.

- Early settlements and agricultural practices develop in the delta, including rice cultivation and fishing.

- Development of early urban centers, such as Chandraketugarh and Wari-Bateshwar.

- Use of cowrie shells as currency.

- Early States and Kingdoms:Emergence of stratified societies, with various communities of cultivators, fishers, craftspeople, religious specialists, traders, and rulers.

- Spread of Indo-European languages.

- Rise and fall of local and regional polities and occasional integration into larger realms such as the Maurya and Gupta empires.

- Establishment and decline of river-based cities like Tamralipti and Lakhnauti-Gaur due to shifts in river courses.

- The emergence of localized forms of control, such as alliances of village leaders in addition to organized states.

- Medieval Period:Arrival and spread of Islam in the delta, leading to the emergence of Muslim Bengalis.

- Development of distinct dialects including Sylheti, Chittagonian and Chakma.

- Establishment of various local kingdoms, and later, the Mughal Empire’s influence and control in the Bengal Delta.

- Mughal Rule (c. 1600 – 1757):Mughal conquest of Bengal and imposition of centralized authority.

- Rise of zamindars as local lords with significant autonomy and varying degrees of grandeur.

- Implementation of a territorial system of administration, including provinces (suba), regions (sarkar) and subdivisions (pargana), and revenue villages (mouza).

- Mughal landholding aristocracy shapes many family names still in use in Bangladesh today

- Decline of Mughal influence after 1700, with the emergence of independent nawabs (princes).

- Early Colonial Period (16th – 18th Centuries):European traders (Portuguese, Dutch, and English) become more prominent in the Indian Ocean trade.

- Portuguese settlements and the spread of Christianity in parts of the Bengal Delta.

- Shift in power dynamics, with Europeans, particularly the British, gaining economic and political influence.

- British East India Company defeats Sirajuddaula in the Battle of Polashi (1757), gaining control of Bengal.

- British Colonial Rule (1757 – 1947):British East India Company gains control over the Bengal Delta.

- Implementation of the Permanent Settlement, transforming land ownership patterns.

- Increase in zamindar power and wealth, including palatial mansions

- Shift in the composition of zamindar class from Muslims to a dominance of Hindu landlords.

- Growth of export-oriented agriculture, especially jute.

- Monetization of the regional economy and its connection to international markets.

- Increased regional disparities.

- Development of a new Bengali cultural identity, including a pride in the Bengali language and a distinct regional style.

- Rise of Indian nationalism.

- Growing demand for Indian independence.

- The Partition of Bengal in 1947 and the creation of Pakistan, with East Bengal becoming East Pakistan.

- Pakistan Period (1947-1971):East Bengal becomes East Pakistan, a province of Pakistan.

- West Pakistan’s dominance over East Pakistan leads to linguistic and regional grievances.

- The Language Movement (Bhasha Andolan) in 1952, fighting for recognition of Bengali language,

- Growing political and economic disparities between East and West Pakistan.

- The rise of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the Awami League, advocating for regional autonomy.

- Military crackdown in 1971 on political dissent.

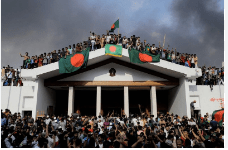

- The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.

- Independent Bangladesh (1971-Present):Emergence of Bangladesh as an independent nation in 1971.

- Early years marked by political instability, famine, and violence.

- Military rule and political coups dominate the period from 1975-1990.

- Rule of Ziaur Rahman (1975-1981) and the expansion of armed forces

- Rise of Islamist political parties and renewed focus on Muslim identity

- Conflict in the Chittagong Hill Tracts from 1975-1997.

- The struggle between “Bengaliness” and “Bangladeshiness”

- Efforts at building a political system and achieving a stable democracy, and the frequent interruptions in that process

- Continued focus on linguistic and cultural identity as essential elements of nation-building.

- The 2006 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank.

- Economic development, including the role of foreign aid and local initiatives.

- Environmental challenges, including floods, cyclones, and the loss of biodiversity

- Debates about national culture and transnational cultural influences.

Cast of Characters

- Murshid Quli Khan: Mughal diwan (top revenue official) who presided over Bengal’s transition to independence from Delhi, becoming an independent nawab. Known for reforming revenue collection and moving the provincial capital to Murshidabad.

- Sirajuddaula: The last independent nawab of Bengal. Attempted to block unauthorized trade by the British, leading to his defeat at the Battle of Polashi in 1757 by the British East India Company.

- Haji Shariatullah: A leader of the Faraizi movement, an Islamic reform movement in the 19th century aimed at purifying Islamic practices and challenging the dominance of the landed aristocracy.

- Khudiram Basu: An Indian revolutionary who was one of the earliest Indian freedom fighters to be executed by British colonial authorities.

- ‘Mastarda’ Surya Sen: An Indian revolutionary freedom fighter and key figure in the Indian independence movement against British rule. Led the Chittagong armory raid.

- Muhammad Ali Jinnah: Leader of the Muslim League and a key figure in the creation of Pakistan. Initially envisioned some form of confederation between India and Pakistan but ended up leading an independent Pakistan.

- Sheikh Mujibur Rahman: Leader of the Awami League and a central figure in Bangladesh’s independence movement. Known as the “Father of the Nation.” Led the country as it’s first president and then as prime minister. He was assassinated in 1975.

- Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani: A politician and Islamic scholar, and a key figure in the politics of East Pakistan and Bangladesh, advocating for the rights of peasants and workers.

- Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: Pakistani politician and president of Pakistan who oversaw the military crackdown in East Pakistan in 1971.

- Ayub Khan: Pakistani army general who served as the second President of Pakistan from 1958 until 1969. His rule is generally seen as a period of authoritarian rule.

- Yahya Khan: Army General and President of Pakistan who presided over the 1971 war, and oversaw the crackdown on civilians in East Pakistan.

- Ziaur Rahman: Major General in the Bangladesh Army who declared independence on the radio in 1971, and later became President of Bangladesh from 1977-1981.

- Khaleda Zia: Bangladeshi politician who served as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh three times, and as the leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. She is the widow of former President Ziaur Rahman.

- Muhammad Yunus: Economist and founder of Grameen Bank. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his work in developing microcredit and poverty alleviation.

- Osama bin Laden: Head of al-Qaeda, a terrorist group whose image became popular among Islamist groups in Bangladesh.

- Maulana Maududi: Founder of the Jamaat-e-Islami in 1941, who clashed with the rulers of Pakistan, advocating for his interpretation of Islamic law to be supreme over all aspects of political and religious life.

- Hamidur Rahman: A painter and art teacher, a student at the College of Arts and Crafts in 1948–50, he became an influential painter and art teacher.

- Shishir Bhattacharjee: Cartoonist known for poking fun in the “Prothom Alo.”

- Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain: A Bengali feminist thinker, writer, and social reformer. She advocated for women’s rights and education.

This timeline and cast of characters provide a comprehensive overview of the historical narrative presented in the provided document, touching on key events, figures, and processes that shaped the modern nation of Bangladesh.

A History of Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a relatively new name for an old land with a history that is not widely known [1]. The region that is now Bangladesh did not become an independent state until 1971 [1]. The history of Bangladesh is marked by a series of significant events and influences, including its geological formation, colonial rule, the partition of Bengal, and the war with Pakistan [1].

Geological History and Early Settlement

- The Bengal delta’s geological history has shaped its society [1].

- The area has a humid, tropical climate with frequent flooding, which is not conducive to preserving material remains of early human settlement [2].

- Early inhabitants likely used materials like wood, bamboo, and mud, which have not survived [2].

- Archaeological interest in the region was limited, with more focus on other parts of the Indian subcontinent [2].

- The various early communities were not Bengalis in the modern sense and spoke languages belonging to different families like Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic and Dravidian [3].

- Languages of the Indo-European family, to which Bengali belongs, began to spread around the fourth century BCE, possibly as languages of rule [3].

- From the fifth century BCE, the Bengal delta became a frontier zone where Sanskritic and non-Sanskritic worldviews met and interacted, shaping the region’s history and culture [4].

Religious and Cultural Frontiers

- The Bengal delta has been a meeting ground for different religious visions [5].

- Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism coexisted for centuries as part of the eastward expansion of Sanskritic culture [6].

- Islam reached the Bengal delta via land routes in the 13th century [7].

- The area saw the growth of shrine-oriented organizations (shomaz) that provided social order, often with communities composed of immigrants who cleared forests and created rice fields [8].

- Religious practices were often shared among different groups, with many deities worshipped by Hindus and Muslims alike [9].

- There has been cultural resistance to strict bipolar categorizations of “Muslim” and “Hindu”, with the Baul community emphasizing spiritual unity [10].

Language and Identity

- The emergence of Bengali as the dominant language was a slow process, with multilingualism being a key characteristic of the region [11].

- Languages like Garo, Khasi, Arakanese, and Koch were widely spoken in the plains [11].

- Bengali evolved from regional forms of Prakrit, with the first writings appearing around 1000 CE [12].

- Other languages were used for rule, ritual, and trade, including Turkish, Persian, Hindustani, Sanskrit, Pali, Arabic, Portuguese, and English [13].

- Distinct Bengali dialects developed, some of which are considered separate languages, such as Sylheti, Chittagonian, and Chakma [14].

- The term ‘Bangladesh’ itself means ‘country of Bengalis’ [11]

- The dominance of the Bengali language reflects its political significance, especially in the 20th century [11].

The Bengal Delta as a Crossroads

- The Bengal delta has always been a mobile and open region, integrated into long-distance trade, pilgrimage, and cultural exchange networks [15].

- It served as a gateway for people and goods from the Ganges plains, Tibet, Nepal, and the Brahmaputra valley [15].

- The region was a meeting point for South-east Asians, North Indians, Sri Lankans, Chinese, Arabs, Central Asians, Persians, Ethiopians and Tibetans [15].

Mughal and British Rule

- The Mughal empire took control of the Bengal delta in 1612, establishing a system of tax collection and foreign administration [16].

- After 1700, the influence of the Mughal court declined, and Bengal became independent under the nawabs [17].

- The British East India Company gained control after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 [17].

- The British sought to transform Bengal’s economy, introducing new administrative and economic policies that sometimes led to disaster, such as the Great Famine of 1769–70, which killed an estimated 10 million people [18].

- The British divided Bengal into a western part and an eastern part in 1905 [19]. This move was seen by many as a calculated effort to weaken the anti-colonial movement [19].

- The 1905 partition of Bengal led to the Swadeshi movement, which advocated for self-reliance and a boycott of British goods [20].

Partition and the Creation of Pakistan

- The partition of India in 1947 resulted in Bengal being divided again, with the eastern part becoming East Pakistan [21].

- Unlike the population exchange in Punjab, the exchange in Bengal was a slower, longer, and more complex process [21].

- The political elite of East Pakistan took exception to the views of the rulers in West Pakistan, especially in relation to the use of Islam as the political idiom and the perception that Bengali Muslims were inferior [22].

- The language issue became a focal point of conflict, with the language movement demanding Bengali as a national language [23].

The Liberation War and Independence

- The language movement, particularly the events of 1952, led to a new type of politician in East Pakistan—the Bengali-speaking student agitator [23].

- The political crises of the late 1960s resulted from the failure of the Pakistani state to narrow the gap between East and West Pakistan [24].

- The 16th of December 1971 is known as Bangladesh’s Victory Day, marking the capitulation of Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh [25].

- The new state faced challenges including dealing with collaborators, rehabilitating war victims, and repairing war damage [25].

Post-Independence Bangladesh

- The new nation embarked on the project of nation-building, with language, regional style and the search for modernity as its main pillars [26].

- The national narrative focused on the victimization of the people by British imperialists, Hindu landlords, and West Pakistani usurpers [27].

- The 1947 Partition was no longer the main focal point of national consciousness and the 1971 war became the pivotal event [28].

- There were differing visions for the future, including a stronger state, a social revolution, or economic liberalization [29].

- The political system that evolved between 1975 and 1990 was one in which the judicial and legislative branches became hostage to military-controlled executive power [30].

- The country returned to parliamentary democracy in 1990 [30].

- Two dominant political forces developed that represented different views of national identity: ‘Bengaliness’ and ‘Bangladeshiness’ [31].

- The idea of ‘Bangladeshiness’ is a legacy of military rule, as is the resurgence of Islamist politicians [32].

- The rights of the country’s indigenous communities were ignored, leading to movements for autonomy and recognition [33].

- Transnational linkages were forged through foreign aid, migration, and advances in telecommunications [34].

- The country has seen increased pressure on its environment due to population growth, industrial production, and waste [35].

Cultural Developments

- Post-independence, there was a major cultural innovation as a national culture was being created [36].

- There was a trend toward a new Islamic cultural repertoire, but this was challenged by more liberal visions [37].

- The Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council was formed in 1988 in protest at the declaration of Islam as the state religion of Bangladesh [38].

- The country also saw the development of a determined women’s movement [38].

- The celebration of Bengali New Year is an important expression of regional identity [38].

- Food is a very central part of the culture [39].

Conclusion

- Bangladesh is a young state with a lengthy and turbulent history, marked by both long-term and more recent processes [40].

- The Bengal delta has always been a crossroads where ideas, people, and goods have mingled, creating a distinct regional culture [40].

- The twentieth century saw political upheaval, demographic shifts, and geopolitical changes that resulted in the creation of Bangladesh [41].

- Today, the inhabitants of the Bengal delta cope with this complex legacy with a flexible and resilient approach [41].

Bangladesh: A Political History

The political systems of Bangladesh have undergone significant transformations, influenced by its history as part of the Mughal and British empires, its time as East Pakistan, and its eventual independence [1, 2].

Early Political Structures

- Prior to the Mughal empire, the Bengal delta experienced political fragmentation, with local rulers holding power [3]. The Mughal state introduced a layer of centralized authority, but local lords, known as zamindars, often remained semi-independent [2, 4].

- The British introduced new legal and property concepts, establishing novel judicial institutions and replacing Persian with English as the official language [5]. They also created educational institutions to train a Bengali elite for the colonial system [5].

Colonial and Post-Colonial Political Developments

- The administrative division of Bengal in 1905 exposed the weakness of political solidarity between religious communities, leading to the formation of distinct political categories of “Muslims” and “Hindus” [6].

- The British administration treated Muslims as a separate political community, encouraging political consciousness based on religious identity and ultimately leading to the creation of the All-India Muslim League [7, 8].

- Electoral politics were introduced in urban areas, gradually expanding to include rural areas, and by 1909, Muslims had the right to vote separately for reserved seats [9, 10].

- By the 1940s, the political landscape was dominated by the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress, with communal politics becoming firmly embedded [11, 12]. The Congress Party was unable to gain control in Bengal [12].

- The push for a separate homeland for Indian Muslims, known as Pakistan, gained momentum, but different ideas about the nature of the state existed, particularly between Bengali and North Indian politicians [13-15].

The Pakistan Era

- After the partition of India in 1947, East Bengal became East Pakistan, and the new Pakistani elite faced the challenge of uniting its citizens [16-18].

- The question of the national language led to significant conflict, with East Pakistan demanding that Bengali be recognized alongside Urdu [18-20].

- The Language Movement of 1952 marked a pivotal moment, with students playing a key role in political resistance [21]. This movement gave rise to a new type of politician in East Pakistan, the Bengali-speaking student agitator [21].

- The United Front’s election manifesto in 1954 included demands for autonomy and economic emancipation, resonating strongly with the rural electorate [22].

- In 1958, the Pakistan army staged a coup, and General Ayub Khan became dictator [23]. This led to the implementation of “basic democracies,” a system designed to bring political processes under bureaucratic control [24].

- The Ayub regime was less willing to give concessions to East Pakistan and favored a centralized system [25]. This resulted in a polarization of left and right within East Pakistan’s politics [26].

- In 1968-69, a wave of unrest swept over Pakistan, and in East Pakistan, it took on Bengali nationalist overtones [27].

- General Yahya Khan took over in 1969, holding elections in 1970, in which the Awami League won a majority of seats [28, 29].

- Negotiations for power transfer failed, leading to the crackdown by the Pakistan army in March 1971 and the start of the Bangladesh Liberation War [30].

Independent Bangladesh

- After the war, the state institutions were weak and in disarray, leading to factional struggles and a politics of patronage [31, 32].

- Bangladesh’s first general elections in 1973 were marred by irregularities, and the Awami League secured a large majority [33].

- In 1975, Bangladesh was in crisis, with debates about the country’s future, including a stronger state, a social revolution or economic liberalization [34].

- Military leaders, who had built their careers during Pakistan’s military dictatorships, seized power after 1975 [35]. These leaders, such as Ziaur Rahman and H.M. Ershad, saw themselves as more capable of running the state than politicians [35, 36].

- Between 1975 and 1990, the political system was characterized by military-controlled executive power, with curtailed civil rights [36].

- The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) was created by Ziaur Rahman in 1978, and after his death in 1981, his widow, Khaleda Zia, became its leader [37, 38].

- Ershad created his own party, the Jatiyo Party in 1986, and like Zia, he also ruled as a military dictator [39].

- A popular movement in 1990 led to the end of military rule and the return to parliamentary democracy [36].

- In 1991, parliamentary elections resulted in a government led by Khaleda Zia and the BNP [40].

- The post-1990 era has been dominated by the rivalry between two main political leaders: Khaleda Zia of the BNP and Sheikh Hasina of the Awami League [41, 42]. These two leaders represent different views of national identity, with the BNP emphasizing ‘Bangladeshiness’ and the Awami League focusing on ‘Bengaliness’ [42, 43].

- The political system continues to be marked by tensions between competing visions of the nation, the rise of Islamist politics, and an inability to accommodate regional autonomy [37].

- The country’s major political groups try to legitimize themselves by reference to the 1971 Liberation War and it’s memory [44].

- The political landscape is often characterized by a struggle between large egos, with mass demonstrations and general strikes being a common part of political life [45].

Bangladesh: A Nation’s Cultural Identity

The development of national culture in Bangladesh is a complex process shaped by its unique history and the interplay of various influences [1, 2]. After gaining independence in 1971, Bangladesh embarked on a project of nation-building, aiming to establish a distinct national culture [3].

Key Aspects of National Culture in Bangladesh

- Language: The Bengali language holds a central place in national identity [3]. The Language Movement of 1952 played a critical role in fostering this sense of linguistic pride and cultural solidarity [4]. After independence, the Urdu script was removed from the public sphere and English usage decreased, with a shift towards Bengali in the education system [5]. The Bangla Academy, established in the 1950s, became an important national institution for the arts and literature [5].

- Regional Identity: A distinct regional culture developed in the Bengal delta over time, influenced by both the states that rose and fell and by the agrarian communities that lived there [6]. A unique regional identity coalesced around being both Muslim and Bengali [6]. This is a crucial hyphenation that became a leitmotif of the delta’s modern history and a source of creative cultural expression [7].

- Multiple Identities: The long-term interplay of different cultural frontiers has resulted in a multi-layered culture in Bangladesh [8]. There is a strong cultural resistance to bipolar categorizations, such as “Muslim” and “Hindu” as mutually exclusive [9]. The Baul community, with their devotional songs, exemplify this emphasis on spiritual unity rather than opposition [9].

- Folk Traditions: Bangladesh’s national culture celebrates and promotes the delta’s folk music, dance, and pictorial traditions [10, 11]. There were many projects to foster handicraft production, leading to the ubiquity of decorative items like jute-rope pot-hangers and block-printed fabrics in the 1970s [11].

- Modernity and Authenticity: The cultural elite in Bangladesh seeks to combine local authenticity with modern appeal in developing a national culture [11]. Religious symbols have largely been replaced by symbols referencing the delta’s natural beauty, such as the national flag with a red disc on a green background and the national emblem of a water lily [11, 12].

- National History: The national historical narrative focuses on the struggles against British imperialists, Hindu landlords, and West Pakistani usurpers [12]. The events of 1971 have become the central point of national consciousness in Bangladesh, displacing the Partition of 1947 as the focus [13].

Cultural Tensions and Transformations

- Clash of Visions: There have been conflicting visions of national identity, namely “Bengaliness” which is closely tied to Bengali language and culture, and “Bangladeshiness,” which emphasizes the Muslim identity [14, 15].

- Emergence of a New Elite: After 1947, a new elite emerged from lower and middle-class backgrounds, educated in Bengali, and this group developed a unique cultural style [16]. Their cultural focus was the Bengal delta, rather than the entire subcontinent or Pakistan [16]. This group was instrumental in the cultural renewal of the 1950s and 1960s, marked by self-confidence and a rejection of cultural models based in Kolkata or West Pakistan [4, 17].

- Mofussil Upsurge: A new cultural model emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, characterized by a nouveau riche aesthetic, with ostentatious displays of wealth and a cultural hero in the streetwise rowdy or “mostan” [18, 19].

- Islamic Sensibility: A growing Islamic sensibility has challenged the vernacular cultural model, due to the return of Islamic symbols, global influences, and a desire for security and moral values [20]. This has led to a new Islamic cultural repertoire and Islamic propriety, which has created tensions with more liberal views of Bangladeshi culture [21].

- Liberal vs. Islamic Visions: The liberal and Islamic visions of Bangladesh culture clash on many fronts, including language, dress, gender relations, festivities and music, with the media and education being important battlegrounds [22].

- Youth Culture: A distinct youth culture has emerged, marked by new music styles like band music, often incorporating folk traditions, but also expressing social critique and darker emotions [23]. This contrasts with new Islamic sensibilities [23].

- Food: Despite cultural differences, most Bangladeshis share a love of food, with rice and fish being staple foods [24]. Traditional cuisine includes a variety of intricate dishes [24].

Continuing Evolution

- The culture of Bangladesh continues to evolve, incorporating global trends while remaining rooted in its historical traditions [2].

- There are debates about the meaning of national culture in the 21st century [2].

- The identity of the people in the delta as “Bengali-Muslim” is still being re-worked in the present day [25].

The national culture of Bangladesh is a dynamic mix of the old and new, with diverse influences shaping its current identity [2]. It is a culture that continues to evolve and adapt while still preserving its unique characteristics [26].

Transnational Bangladesh

Bangladesh has a history of openness to the outside world, with long-standing connections to various regions through trade, travel, and cultural exchange [1, 2]. In the post-independence era, these transnational links have grown in significance, playing a crucial role in shaping the country’s economic, social, and cultural landscape [3, 4].

Key drivers of transnational connections

- Foreign Aid: Following the 1971 Liberation War, Bangladesh became a major recipient of foreign aid, which was instrumental in its economic recovery [3, 5]. This aid came with conditions, such as the privatization and liberalization of the economy, and also brought a large number of expatriates into the country, including consultants, volunteers, and diplomats [5].

- NGOs: Foreign aid also led to the proliferation of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which became a key mechanism for implementing development policies [6]. Some of these NGOs grew into large national and international organizations, such as BRAC and the Grameen Bank [6, 7]. The Grameen Bank’s microcredit program, for example, became an influential model for development initiatives globally [7, 8].

- Migration: Bangladesh has a long history of migration, and the patterns of migration changed significantly in the 1990s with the rise in migrant remittances [9]. There are three main types of emigration [10]:

- Overseas labor migration: Bangladeshis, especially from the Sylhet, Noakhali and Chittagong districts, have been employed on ships for centuries and have formed communities in port cities [10]. This trend continued in the mid-20th century when many Bangladeshi men migrated to Britain and later, to the oil-rich states in West Asia to work [10, 11].

- Middle-class educational and job migration: The expansion of the national elite led to a rise in the number of families sending their children to study abroad, particularly in North America, Australia, and Europe [12]. These migrants often secured well-paid jobs and sent money back to Bangladesh [12].

- Unauthorized labor migration to India: Large numbers of Bangladeshis migrated illegally to India, often living in slums and facing the risk of deportation [13]. Despite their poverty, the sheer number of these migrants led to considerable remittances [13, 14].

- These migrations are driven by the strength of kinship ties, with families often making decisions about who should go abroad based on their potential to send money home [14].

- Connectivity: Advances in telecommunications have revolutionized the way information travels in the delta [15]. Mobile phones, for example, have spread rapidly, enabling communication even in remote rural areas, and the internet has allowed the middle classes to participate in global cyberspace [4, 15].

Consequences of Transnational Connections

- Economic Impact: Remittances from migrants became a major support for the national economy, diminishing reliance on foreign aid [9, 14]. In 2006, remittances recorded by the Bangladesh Bank reached $5 billion [9].

- Social Transformation: Transnational links have created a more cosmopolitan society, with Bangladeshi communities all over the world [4]. These communities serve as brokers of new ideas and wealth [4].

- Cultural Exchange: The interactions between Bangladeshis and other cultures have influenced the delta’s culture, and these connections have resulted in a more complex, fragmented, and vibrant cultural scene [16, 17].

- Political Influence: The connections between Bangladeshis living abroad and their relatives back home can lead to political influences, as people overseas develop opinions on the country’s political situations [4].

Challenges and Complexities

- Dependency: Despite the economic benefits of remittances, there is concern that the country is becoming overly reliant on this source of income, and that it may not continue indefinitely, as the children of migrants often do not have the same ties to Bangladesh [14].

- Illegal Migration: Unauthorized migration, particularly to India, has led to tensions and deportations, further complicating the relationship between the two countries [13, 14].

- Power dynamics: Foreign aid donors sometimes sought to influence government policies [5]. Also, the state has had limited capacity to process aid flows [6].

- Uneven distribution: The benefits of transnational connections are not evenly distributed, with some groups and individuals profiting more than others [12].

Overall, transnational links have become an integral part of the social, economic, and political fabric of Bangladesh, and they continue to shape its development in the 21st century [4].

Bangladesh’s Environmental Crisis

Bangladesh faces a range of environmental challenges stemming from its unique geographical location, high population density, and human activities [1]. The country’s low-lying deltaic environment makes it particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and natural disasters [1, 2].

Key Environmental Issues

- Land-Water Dynamics: The country is located on a constantly shifting frontier between land and water [1]. Floodplains cover about 80% of Bangladesh [3]. This dynamic environment is shaped by the complex interplay of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, as well as the monsoon climate [3-5].

- Population Density: With over 1,000 people per square kilometer, Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world [1]. This puts immense pressure on the environment, leading to the overuse of resources and increased pollution [6, 7].

- Deforestation: The clearing of forests for agriculture, settlements, and logging has led to significant deforestation, especially in the Chittagong Hill Tracts [8]. This has resulted in soil erosion, declining soil fertility and further environmental damage [8].

- Water Pollution: Industrial waste, human waste, and agricultural runoff contaminate the delta’s rivers and lakes [6]. About 90% of human waste ends up in rivers and lakes due to a lack of proper sewerage systems [6]. This is further compounded by the influx of pollutants from rivers that flow into Bangladesh from India [6].

- River Diversion: The diversion of water from the Ganges River by India at the Farakka barrage has had adverse effects on the ecology and economy of southwestern Bangladesh, resulting in low water levels, diminished soil moisture and poor water quality [4, 5, 9]. This has also caused environmental refugees to migrate into India [9].

- Loss of Biodiversity: Human interference has led to the collapse of many aquatic life forms [10]. The black soft-shell turtle is now extinct in the wild and only survives in a pond [10]. Three species of vultures are also believed to be extinct [11]. The hilsa fish, a long-important part of the Bangladeshi diet, is also in decline [10]. The Bengal rainforest that once covered the delta is long gone, replaced by rice fields [11]. The Sundarbans, a vital wetland area, is experiencing degradation with decreased vegetation, and a reduction in animal and fish populations [12, 13].

- Climate Change: Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, deeper flooding, increased cyclone frequency, and crop losses due to higher temperatures [2]. Land subsidence is also believed to be worsening the issue [2]. These factors may lead to climate exiles in coastal areas by the middle of the century [2].

- Waste Management: The delta struggles to cope with huge amounts of non-biodegradable waste such as plastic [6].

- Water Hyacinth: The water hyacinth, an imported weed, has choked waterways and rice fields [14]. Despite attempts to eradicate it, it has become a persistent problem [14, 15].

Environmental Issues and Human Impact

- Agriculture: Rice cultivation, while well-suited to the delta’s environment, can also contribute to environmental issues when not managed sustainably [16]. The use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides can lead to water pollution [6].

- Industry: Industrial production contributes to environmental damage through pollution and waste [6].

- Energy: The country’s dependence on biomass for energy needs contributes to deforestation [17]. There are ongoing debates about the desirability of exporting gas and the environmental impact of exploiting coal reserves [18].

- Health: Contaminated water sources contribute to the spread of diseases [6]. The use of pesticides and other pollutants can also have a negative impact on human health [6, 10].

Environmental Activism and Conservation

- Environmental Movement: An environmental movement has taken shape, focusing on issues such as air and water pollution, land degradation, and climate change [2]. This movement was successful in getting the government to ban polythene bags, although the ban has been difficult to enforce [17].

- Protection Efforts: There have been efforts to protect endangered species through hatcheries and conservation declarations, notably regarding sea turtles on Narikel Jinjira [8, 12, 19]. The Sundarbans have also become a focus for conservation efforts [12].

- Community Action: In some cases, local communities have organized to prevent the implementation of harmful development projects and promote sustainable alternatives [20].

Overall, Bangladesh faces a complex set of interconnected environmental problems that require comprehensive and sustainable solutions [7]. These challenges are further compounded by social, economic, and political factors, and they require the active involvement of the government, civil society, and the international community [20].

By Amjad Izhar

Contact: amjad.izhar@gmail.com

https://amjadizhar.blog

Affiliate Disclosure: This blog may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you click on the link and make a purchase. This comes at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products or services that I believe will add value to my readers. Your support helps keep this blog running and allows me to continue providing you with quality content. Thank you for your support!

Leave a comment