This text excerpts from a history of Afghanistan, covering a vast period from 1260 to the present. It details the geography of Afghanistan, including its river systems and regions like Badghis, and explores the succession of dynasties that ruled the country, such as the Kushano-Sasanian, Timurid, and Durrani empires. The excerpt further examines the religious and ethnic diversity of Afghanistan, noting the presence of various faiths alongside Islam, and analyzes the impact of British and Soviet policies on Afghan history, culminating in the tumultuous events of the 20th and 21st centuries. Finally, the text includes a glossary of terms relevant to Afghan history and culture.

A History of Afghanistan: 1260-Present

Review Questions

- Describe the concept of “ghulams” in Islamic armies. How did they differ from slaves in the European sense? Ghulams were indentured levies conscripted into Islamic armies. Unlike European slaves, they were often recruited from subjugated populations and converted to Islam. They formed elite, loyal military units and held a privileged status compared to other soldiers and commoners. Their commanders often wielded significant political power.

- What was the “world of honor” in Afghan society? How did one acquire honor, and what were the consequences of shame (sharm)? The “world of honor” in Afghan society centered on warrior virtues and public reputation. Honor could be ascribed by birth or lineage or achieved through bravery, generosity, hospitality, and religious piety. Shame, on the other hand, was a severe social consequence resulting from acts like cowardice, disrespecting elders, or bringing disgrace upon oneself or one’s family.

- Explain the significance of the Sind treasure for Ahmad Shah Durrani. How did it impact his rise to power? The Sind treasure provided Ahmad Shah with the financial resources he needed to consolidate power. He used it to reward his followers, buy loyalties, and assemble a formidable army. This allowed him to overpower rival Afghan and Baluch tribes, leading to the establishment of the Durrani Empire.

- What was the outcome of the First Anglo-Afghan War? How did it shape future Anglo-Afghan relations? The First Anglo-Afghan War ended in a humiliating British retreat from Kabul. It sowed deep mistrust between the two nations, leading to further conflict and shaping British policy towards Afghanistan for the next century. It fueled the “Great Game” between Britain and Russia for influence in Central Asia.

- How did Dost Muhammad Khan centralize power during his reign? What were the key features of his administrative reforms? Dost Muhammad Khan centralized power by appointing his sons as provincial governors and ministers, consolidating control within his family. He also revived the tradition of public audiences, acting as judge and jury, and reduced the power of autonomous hereditary rulers, creating a more centralized autocracy.

- What were the main motivations behind the Second Anglo-Afghan War? How did British policy towards Afghanistan shift after the war? The Second Anglo-Afghan War stemmed from growing Anglo-Russian rivalry in Central Asia. The British feared Russian influence over Afghanistan and sought to install a pro-British ruler in Kabul. After the war, British policy became more focused on controlling Afghanistan’s foreign relations while granting internal autonomy.

- How did Habib Allah Khan navigate the challenges of his reign? What were some of his notable reforms? Habib Allah Khan navigated a politically turbulent time by balancing the interests of various tribal factions. He introduced some modern reforms, including the establishment of the first girls’ school, but maintained a cautious approach to modernization to avoid provoking conservative elements.

- Describe the key events leading to the fall of the Afghan monarchy in 1978. What were the long-term factors contributing to the instability? The Afghan monarchy fell in 1978 due to a coup led by communist officers. Underlying this event were long-term factors like social and economic inequalities, ethnic tensions, and the growing influence of communist ideology, particularly among educated Afghans and military officers.

- What role did madrasas play in the formation of the Taliban? How did their interpretation of Islam shape the Taliban’s ideology? Madrasas, particularly those in Pakistan, played a significant role in shaping the Taliban’s ideology. These institutions provided a strict and often literal interpretation of Islam, which the Taliban used to justify their austere social policies, harsh punishments, and rejection of modern values.

- How did the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan impact the country? What were its long-term consequences? The Soviet invasion had a devastating impact on Afghanistan, leading to widespread death, destruction, and displacement. It also fueled the rise of militant groups like the mujahideen and ultimately contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union. The legacy of war and instability continues to haunt Afghanistan today.

Essay Questions

- Analyze the role of tribal dynamics in shaping Afghan history from 1260 to the present.

- Compare and contrast the reigns of Ahmad Shah Durrani and Dost Muhammad Khan, focusing on their achievements, challenges, and legacies.

- Discuss the impact of Anglo-Afghan relations on the development of modern Afghanistan, examining both the positive and negative aspects.

- Evaluate the modernization efforts of Afghan rulers in the 20th century. To what extent were they successful, and what were the main obstacles they faced?

- Analyze the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Afghanistan, considering its historical roots, social and political context, and implications for the country’s future.

Briefing Document: A History of Afghanistan from 1260 to the Present

This briefing document reviews key themes and information from excerpts of the book “Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present.” The source provides a broad overview of Afghan history, focusing on political and social dynamics, highlighting the role of tribal structures, religious influences, and external pressures in shaping the nation’s trajectory.

Key Themes:

- The Significance of Tribalism: Afghan society is deeply rooted in tribal structures, impacting political power, social organization, and cultural norms. The text emphasizes the role of tribes like the Abdalis (later Durranis), Ghilzais, and various Pashtun groups in vying for dominance and influencing Afghan politics. The dynamics of honor, shame, and blood feuds within this tribal context are illustrated through historical anecdotes, such as the story of Hayat Khan Saddozai and Murad Bibi (p.73).

- The Role of Islam: Islam plays a pivotal role in shaping Afghan identity and governance. The text details the influence of various Islamic sects and orders like the Hanafi Sunnism, Shia Islam, and Sufi orders like the Mujadidi and Naqshbandiyya. The struggle between secular and religious forces, the fluctuating role of Islamic law in the legal system, and the rise of Islamic political movements like the Taliban are explored throughout the historical narrative.

- External Influences and Interventions: Afghanistan’s geostrategic location has subjected it to continuous external pressures and interventions from regional and global powers. The text details the impact of the Mughal Empire, Persia, the British Empire, the Russian Empire/Soviet Union, and the United States on Afghan politics and society. These external interactions are analyzed in the context of Afghan resistance, adaptation, and the ongoing quest for national sovereignty.

Important Ideas and Facts:

- The Rise and Fall of Afghan Sultanates (1260-1732): This period witnessed the emergence of Afghan dynasties like the Khalji Sultanate of Delhi, highlighting the military prowess and complex relationship of Afghan tribes with the Delhi Sultanate (p. 53-60). The text details the role of ghulams (slave soldiers) in shaping political power dynamics and the inherent tension between centralized rule and tribal autonomy.

- The Durrani Empire and its Legacy: The founding of the Durrani Empire by Ahmad Shah Durrani marked a pivotal moment in Afghan history, unifying various Pashtun tribes and establishing Afghanistan as a major regional power. The text covers Ahmad Shah’s conquests, his administrative reforms, and the challenges of succession within the Durrani dynasty (p. 102-113).

- The Anglo-Afghan Wars and the Great Game: The 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by intense rivalry between the British and Russian Empires for influence in Central Asia, with Afghanistan becoming a central battleground. The text provides detailed accounts of the Anglo-Afghan Wars, highlighting British motivations, Afghan resistance, and the lasting impact of these conflicts on Anglo-Afghan relations (p. 190-411).

- Modernization Attempts and Political Instability: The 20th century witnessed various attempts at modernization and reform in Afghanistan, led by rulers like Amanullah Khan, Nadir Shah, and Daoud Khan. These efforts often faced resistance from conservative elements within Afghan society. The text details the successes and failures of these reform movements, highlighting the enduring tensions between tradition and modernity in Afghan society (p. 412-594).

- The Soviet Invasion and the Rise of the Taliban: The Soviet invasion of 1979 marked a turning point, leading to a brutal civil war and the emergence of the mujahideen, supported by various external powers. The subsequent rise of the Taliban, their harsh interpretation of Islamic law, and their eventual overthrow by the US-led invasion in 2001 are crucial aspects of recent Afghan history (p. 604-683).

Quotes from the Source:

- On the Afghan concept of honor: “The world of honour is rooted in the exalting of manly, warrior virtues and the pursuit of public honour…The flip side of this honour-centric world view is the need to avoid sharm – shame or disgrace – or a ‘blackened face’.” (p. 13)

- On the role of ghulams: “The ghulams thus provided a ruler with a corps of loyal troops that were bound to him by oath and patronage and that offset the power of the sultan’s tribe and other powerful factions at court.” (p. 53)

- On Ahmad Shah Durrani’s rise to power: “The Sind treasure fortuitously provided Ahmad Shah with a substantial war chest that he used to buy loyalties and reward his ghazis.” (p. 106)

- On Dost Muhammad Khan’s strategic thinking: “In private, the Amir told Harlan it had been a great mistake to allow himself to be drawn into the web of Anglo-Russian intrigue.” (p. 220)

- On the impact of Soviet aid: “The surge in Soviet aid led to an influx of hundreds of Soviet and Warsaw Pact technical and military advisers, while Army and Air Force officers, military cadets and students received scholarships to study in the USSR, where they were exposed to Communist ideology and propaganda.” (p. 558)

This briefing document provides a synthesized overview of key information and themes from the provided excerpts of “Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present.” A deeper dive into the source material will reveal further insights into the complexities of Afghan history and the factors that continue to shape its present and future.

Afghanistan FAQ

What are the major languages and calendars used in Afghanistan?

Languages: Pashto and Dari (Afghan Persian) are the official languages of Afghanistan. Dari is more widely spoken and serves as the lingua franca in many parts of the country. Other languages spoken include Uzbek, Turkmen, Balochi, and Pashayi.

Calendars: Three calendars are used in Afghanistan. The most common is the Gregorian calendar (CE). The Islamic lunar calendar (Hijri) is used for religious purposes. The Afghan/Persian solar calendar (Shamsi) starts on the Spring equinox (around March 21st) and is also widely used.

How is honor perceived in Afghan culture?

Honor is a central concept in Afghan society, especially among the Pashtuns. It’s a complex system based on upholding manly virtues, courage, generosity, hospitality, and religious piety. Honor can be inherited or earned. Achieving honor often involves bravery in battle, generosity, hospitality, public service, and being a devout Muslim. Shame (sharm) is the opposite of honor and encompasses actions such as disrespecting elders, cowardice, or public disgrace.

What was the role of the ghulams in Islamic armies?

Ghulams were soldiers recruited from conquered populations, often non-Muslims who converted to Islam. Unlike tribal levies with fluctuating loyalties, ghulams swore allegiance to the ruler, providing a core of loyal troops. They received superior training and weapons, forming a professional fighting force. Over time, ghulam commanders gained influence, even becoming kingmakers or establishing their own dynasties, as seen with the Ghaznavids.

How did the Khalji Sultanate in Delhi interact with its subjects?

The Khalji dynasty, of Afghan origin, ruled a predominantly Hindu population in Delhi. They maintained a degree of cultural isolation by living in separate quarters (mahalas) and practicing endogamy (marrying within their own tribe). Despite internal conflicts and blood feuds, the Khaljis were a powerful military force. They successfully repelled Mongol invasions, safeguarding northern India from the devastation experienced by Afghanistan and Persia.

Who was Murad Bibi and what was her significance in Afghan history?

Murad Bibi was a powerful female figure among the Abdali Pashtuns in the early 18th century. As the widow of a tribal leader, she exercised considerable authority and played a pivotal role in tribal affairs. Known for her strength and determination, she defied norms by demanding retribution for her son’s death, ultimately choosing the next tribal leader. Her story highlights the complexities of power and gender roles in Afghan tribal society.

How did Ahmad Shah Durrani come to power in Afghanistan?

Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of the Durrani Empire, rose to prominence after the assassination of the Persian ruler Nadir Shah. Having served as Nadir Shah’s trusted general, Ahmad Shah inherited a significant portion of his army and treasury. This allowed him to secure alliances, assert his authority over Afghan tribes, and declare an independent Afghan kingdom.

What were the key factors that led to the First Anglo-Afghan War?

The First Anglo-Afghan War stemmed from British anxieties over Russian expansion in Central Asia, known as the “Great Game.” The British East India Company, fearing a Russian invasion of India through Afghanistan, sought to install a pro-British ruler in Kabul. This led to interference in Afghan affairs, culminating in the disastrous First Anglo-Afghan War. Key events included the contentious appointment of Shah Shuja` and the subsequent Afghan uprising against British influence.

How did Dost Muhammad Khan change the Afghan government?

Dost Muhammad Khan, a key figure in 19th-century Afghanistan, significantly transformed the country’s government. He moved away from ruling through autonomous local chiefs and established a centralized system with his sons as ministers and governors. He also revived public audiences where he personally addressed complaints and acted as judge. This transition to a centralized autocracy, resembling an Arab sheikhdom, had long-lasting implications for Afghan governance.

A Concise History of Afghanistan

Timeline of Main Events:

Pre-1732:

- 977-1186: Ghaznavid dynasty rules, with Ghazni as their capital. Khalaj serve as ghulams (soldiers of fortune) in the Ghaznavid army.

- 1260-1732: Several Afghan sultanates, notably the Khalji Sultanate of Delhi, rise to power.

- Late 16th Century: Safavid Shah appoints a Mir-i Afghaniha to administer Afghan tribes in Farah.

- 1709: Mir Wais Hotaki leads a successful rebellion against the Safavids, establishing an independent Hotaki dynasty in Kandahar.

- 1722: The Hotaki dynasty conquers Persia, but their rule is short-lived.

- 1729: Nadir Shah Afshar, a former ghulam, overthrows the Hotaki dynasty in Persia.

- 1738: Nadir Shah conquers Kandahar, incorporating the Afghan tribes into his army.

Nadir Shah and the Afghans, 1732–47:

- 1747: After the assassination of Nadir Shah, Ahmad Shah Durrani is elected leader by a council of Afghan tribal chiefs, marking the beginning of the Durrani Empire.

Afghan Sultanates, 1260–1732:

- 18th Century: Ahmad Shah Durrani expands the Durrani Empire, conquering territories that encompass modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of India and Iran.

- Late 18th Century: Following Ahmad Shah’s death, the Durrani Empire faces internal strife and fragmentation, with various factions vying for power.

Afghanistan, 1819–1929:

- Early 19th Century: The Barakzai clan, led by Dost Muhammad Khan, emerges as the dominant force in Afghanistan, establishing the Barakzai dynasty.

- 1839-42: The First Anglo-Afghan War ends in a British defeat and the restoration of Dost Muhammad Khan as Amir.

- 1878-80: The Second Anglo-Afghan War results in British control over Afghan foreign policy, but not direct rule.

- Late 19th Century: Abd al-Rahman Khan, a grandson of Dost Muhammad Khan, becomes Amir and consolidates power through ruthless policies, centralizing the government and establishing firm borders.

- Early 20th Century: Habib Allah Khan, son of Abd al-Rahman Khan, succeeds as Amir and introduces limited reforms, but faces growing calls for further modernization and democracy.

Backs to the Future, 1929–33:

- 1919: Amanullah Khan ascends to the throne and declares full independence from Britain, leading to the Third Anglo-Afghan War, which ends in Afghan victory.

- 1920s: Amanullah Khan implements ambitious reforms aimed at modernization and social change, but faces resistance from conservative elements within society.

- 1929: Amanullah Khan is overthrown due to rebellion fueled by conservative opposition to his reforms. A period of instability ensues, with various factions and leaders vying for control.

- 1929: Habib Allah Kalakani (Bacha-yi Saqau), a Tajik folk hero, seizes Kabul, but his rule is short-lived.

- 1929-33: Nadir Shah, a former general under Amanullah Khan, gathers support and leads a successful campaign to restore the monarchy, establishing the Musahiban dynasty.

Afghanistan, 1933–78:

- 1930s-1970s: The Musahiban dynasty continues to rule Afghanistan, focusing on economic development and cautious social reforms.

- 1933: Nadir Shah is assassinated, and his son, Zahir Shah, becomes King, ruling for over four decades.

- 1950s-1970s: Afghanistan experiences a period of relative peace and stability, receiving substantial foreign aid from both the Soviet Union and the United States.

- 1964: A new constitution is adopted, introducing a more democratic system, although the King and the Musahiban family retain significant power.

- 1973: Muhammad Da’ud Khan, a former Prime Minister and the King’s cousin, stages a coup, abolishes the monarchy, and declares Afghanistan a republic.

Afghanistan, 1978–2001:

- 1978: The Saur Revolution, led by the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), overthrows Da’ud Khan and establishes a socialist government.

- Late 1970s – 1980s: The Soviet Union invades Afghanistan to support the struggling PDPA government, facing resistance from various Mujahideen groups.

- 1989: The Soviet Union withdraws from Afghanistan after a decade of costly war, leaving behind a fragmented and war-torn country.

- 1992: The Mujahideen factions capture Kabul and overthrow the PDPA government. The country descends into a brutal civil war between rival warlords.

- 1996: The Taliban, a radical Islamist group, emerges from the chaos, capturing Kabul and establishing control over most of Afghanistan.

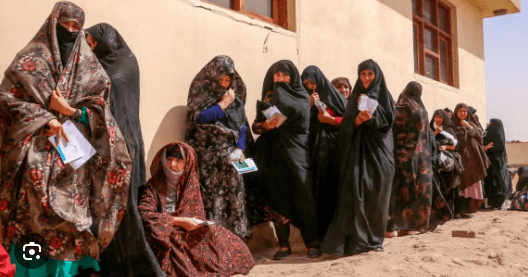

- 1996-2001: The Taliban imposes a strict interpretation of Islamic law, suppressing human rights, particularly those of women, and providing sanctuary to terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda.

Afghanistan, 2001–Present:

- 2001: Following the 9/11 attacks, a US-led international coalition invades Afghanistan, toppling the Taliban regime and installing a new government.

- 2001-Present: The international community engages in a long and challenging process of rebuilding Afghanistan, promoting democracy, economic development, and human rights. However, the country continues to face a persistent insurgency from the Taliban and other militant groups.

- 2021: The US withdraws its forces from Afghanistan, leading to a swift Taliban takeover and the collapse of the Afghan government.

Cast of Characters:

Early Figures:

- Sabuktigin (942-997): Founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty. He was originally a ghulam general who rose to prominence and established his own kingdom centered in Ghazni.

- Jalal al-Din Firuz (r.1290-96): First Khalji Sultan of Delhi. Known for his military prowess and cultural isolation from his Hindu subjects.

- ‘Ala’ al-Din (Juna Khan) (r. 1296–1316): Successor of Jalal al-Din Firuz and a powerful Khalji Sultan. Famous for his military achievements, including victories against the Mongols.

- Mir Wais Hotaki (d. 1729): Founder of the Hotaki dynasty in Kandahar. Led a successful rebellion against the Safavid Empire and established an independent Afghan state.

- Nadir Shah Afshar (1688-1747): A brilliant military commander and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty in Persia. He overthrew the Hotaki dynasty and incorporated the Afghan tribes into his army.

Durrani Empire:

- Ahmad Shah Durrani (1722-1772): Founder of the Durrani Empire. Elected as leader by Afghan tribal chiefs after the assassination of Nadir Shah, he expanded his rule over vast territories and is considered the father of modern Afghanistan.

- Timur Shah Durrani (1767-1793): Son and successor of Ahmad Shah Durrani. Faced numerous rebellions and challenges during his reign, but managed to maintain the integrity of the empire for a time.

- Zaman Shah Durrani (1770-1844): Grandson of Ahmad Shah Durrani and a ruler known for his ambitious military campaigns and efforts to regain lost territories. Deposed and blinded by his brother Mahmud Shah.

- Shah Shuja‘ al-Mulk (1785-1842): Another grandson of Ahmad Shah Durrani who briefly ruled as Shah. Known for his alliance with the Sikhs and the British during the First Anglo-Afghan War.

Barakzai Dynasty:

- Dost Muhammad Khan (1793-1863): Founder of the Barakzai dynasty. A shrewd and resilient ruler who fought against both the Sikhs and the British to secure his position as Amir.

- Sher Ali Khan (1823-1879): Son of Dost Muhammad Khan and a ruler who sought to modernize Afghanistan. His reign was marked by conflict with Britain, culminating in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

- Abd al-Rahman Khan (1844-1901): Grandson of Dost Muhammad Khan who came to power with British support after the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Known for his brutal policies and consolidation of power, centralizing the government and establishing firm borders.

- Habib Allah Khan (1872-1919): Son of Abd al-Rahman Khan. Continued his father’s policies of cautious reform while maintaining relations with the British.

- Amanullah Khan (1892-1929): Son of Habib Allah Khan and a progressive ruler who declared full independence from Britain in 1919. Implemented ambitious reforms aimed at modernization and social change, but faced resistance from conservative elements within society, ultimately leading to his overthrow.

Musahiban Dynasty and Later Figures:

- Habib Allah Kalakani (Bacha-yi Saqau) (1890-1929): A Tajik folk hero who briefly seized Kabul during the period of instability following Amanullah Khan’s overthrow.

- Nadir Shah (1883-1933): A former general under Amanullah Khan who led a successful campaign to restore the monarchy, establishing the Musahiban dynasty. Focused on stabilizing the country and reversing some of Amanullah Khan’s more radical reforms.

- Muhammad Zahir Shah (1914-2007): Son of Nadir Shah. Ruled as King for over four decades, overseeing a period of relative peace and stability. Deposed by his cousin Muhammad Da’ud Khan in 1973.

- Muhammad Da’ud Khan (1909-1978): A former Prime Minister and the King’s cousin. Staged a coup in 1973, abolishing the monarchy and declaring Afghanistan a republic. Pursued a policy of non-alignment and sought to modernize the country.

- Nur Muhammad Taraki (1917-1979): A prominent communist leader and one of the founders of the PDPA. Became the first President of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan after the Saur Revolution.

- Hafizullah Amin (1929-1979): A hardline communist leader within the PDPA. Seized power after orchestrating the death of Taraki. His policies and brutal methods alienated many Afghans and contributed to the Soviet intervention.

- Babrak Karmal (1929-1996): Another PDPA leader who became President with Soviet support after the Soviet invasion. Implemented more moderate policies but struggled to gain popular support.

- Mullah Omar (1959-2013): The reclusive leader of the Taliban. A former Mujahideen commander who emerged from the chaos of the civil war to establish the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996.

- Hamid Karzai (born 1957): A prominent Pashtun leader who became the first President of Afghanistan after the US-led invasion in 2001. Played a key role in the post-Taliban political transition.

- Ashraf Ghani (born 1949): A former World Bank official who served as President of Afghanistan from 2014 until the Taliban takeover in 2021. Focused on economic development and good governance but struggled to contain the Taliban insurgency.

This timeline and cast of characters provides a concise overview of the major events and key individuals covered in the provided source. However, it’s important to note that this is just a starting point, and further research may be required for a more in-depth understanding of Afghan history.

The Myth of Afghan Unity

Afghanistan has never been ethnically cohesive, and the size and percentage of the country’s ethnolinguistic groups have long been a source of political manipulation [1]. According to a Polish linguistic survey conducted in the 1970s, Afghanistan has between 40 and 50 languages belonging to seven separate linguistic groups [2].

The Pushtuns, also known as Afghans or Pathans, are the largest ethnic group and have been the dominant political power in modern Afghanistan. However, even by the most generous estimates, they make up only about one-third of Afghanistan’s population [1]. There are more Pushtuns in Pakistan than in Afghanistan [1]. The Pushtuns consist of dozens of tribes that historically lived in the plains and mountains straddling the modern Afghan–Pakistan frontier [1]. Before European colonial intervention, this region was the original Afghanistan, or the land of the Afghan tribes [1]. It consisted of the regions east of the Helmand river and stretched as far east as Jalalabad, the Kunar valley, Swat, and Chitral [1].

Imperial and Afghan nationalist-monarchist discourse claims that modern Afghanistan was founded with the “election” of Ahmad Shah Durrani in Kandahar in 1747, and this discourse has tended to emphasize the Afghanness, or Pushtunness, of the dynasty [3]. This narrative ignores key historical factors that gave rise to the Durrani dynasty [3]. It also glosses over the uncomfortable fact that the ‘Abdali tribe and its dynasties were essentially Persianate [3]. The alliance with Safavid Persia was arguably the key element that facilitated the rise of both the Hotaki and Saddozai kingdoms [3]. This alliance came about partly because urbanized ‘Abdalis in Kandahar, though referred to as Afghan, spoke a local dialect of Farsi [3]. The ethnogenesis of the ‘Abdali tribe more than likely derived from the Persian-speaking peoples of medieval Ghur and Gharchistan [3].

The rise of the ‘Abdalis to political prominence as clients of a Persian, Shi‘a monarchy has been largely airbrushed out of modern Afghan historiography and ignored by Western historians [4]. For many Afghans, especially monarchists, it is an embarrassment, because from the early twentieth century, successive governments deliberately promoted a national identity constructed on three foundations [4]:

- The Durrani dynasty’s adherence to Hanafi Sunnism, which was on occasion accompanied by anti-Shi‘a and anti-Persian sentiment

- Pushtunness and the Pushtu language

- Afghan resistance to, and independence from, the dominant imperial powers of the region, including Persia [4]

All of these pillars are based on fallacies and required a significant rewriting of Afghanistan’s early history, from school textbooks to historiography [4]. One reason that Afghan historians favor 1747 as the foundation of modern Afghanistan is that it avoids referring back to the previous two and a half centuries of the Saddozai–Safavid alliance [4]. It also avoids the uncomfortable fact that before 1747, Kandahar, which Afghan monarchists would later promote as the dynastic and spiritual capital of Afghanistan, was for many decades an integral part of the Persian province of Khurasan and that the ‘Abdalis were a Persianate tribe [4].

A listing of the principal dynasties of Afghanistan from 555 BCE to 1859 is included in the sources [5].

Afghanistan’s Rivers and Irrigation Systems

Afghanistan has five major river basin systems:

- The Kabul River

- The Amu Darya River

- The Balkh Ab River

- The Murghab-Hari Rud River

- The Helmand-Arghandab River [1]

All of Afghanistan’s rivers are used for irrigation to some degree. However, most of the irrigation systems are unlined, and only a few have steel control gates or concrete-lined banks and canals. Most diversion structures are built from compacted earth or stone. [2]

The maintenance of irrigation canals is very labor-intensive, and local stakeholders gather to clear silt from their canals and fix diversion structures in the spring and autumn. Community-appointed water bailiffs called mirabs are responsible for managing and distributing water within irrigation networks. Another traditional irrigation source comes from underground springs that flow through underground channels called karez. [2]

All of Afghanistan’s major water-storage facilities are in southern Afghanistan. Smaller dams are found on minor rivers throughout the country. These dams provide water for irrigation and a limited and inconsistent supply of electricity to neighboring urban centers. All of the dams and equipment in Afghanistan are aging and need to be repaired. Two of the most important dams, the Darunta on the Arghandab River and the Kajaki on the Helmand, are not under government control and are currently controlled by insurgents. [3]

The Indian-funded Selma Dam on the Hari Rud was finally opened in 2016 after the project was delayed from the 1970s due to the Soviet invasion and the civil war that followed. The current government plans to build at least fifteen more major dual-use storage facilities, although it is unclear where the funding for such an ambitious plan will come from. [3]

The Amu Darya River, also known as the Oxus, is one of the most important rivers in Central Asia. It rises in the Pamir range in northeastern Afghanistan on the border with China and Tajikistan, and it forms Afghanistan’s northern international frontier. [4] Historically, Afghanistan has not used the Amu Darya for irrigation due to pressure from the USSR and, more recently, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. These countries divert water from the Amu Darya into canals that irrigate the cotton fields of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. [4]

The Balkh plains, which extend from Khulm to Maimana, are irrigated by rivers that originate in the Tir Band-i Turkistan and the Hazarajat. However, all of the rivers in this area dry up before they reach the Amu Darya. [5] The Balkh Ab is the most important river in this region, and its source is the Band-i Amir lakes, a series of remarkable blue lakes located north of Bamiyan. The Balkh Ab feeds a vast and ancient irrigation system in its lower course known as the Hazhda Nahr, or Eighteen Canals. The Hazhda Nahr creates an inland delta that extends from north of Aqcha to west of Mazar-i Sharif. [5]

Only ten canals are still operational today, but despite neglect, poor management, and rising unlawful water extraction, double cropping is still widespread at the beginning of the Hazhda Nahr network. Large quantities of rice and cotton are cultivated in this area, and the melons from this region are known for their sweetness and massive size. The chul, a belt of high loess dunes, is located along the northern face of the Tir Band-i Turkistan. The chul is one of the most important rain-fed wheat-growing areas in the country. Walnuts and mulberries are plentiful in the lower valleys of this mountain range, which also produces a significant amount of raw silk. Marijuana and opium are frequently cultivated on the plains to the north. [5]

The Murghab River, which flows into the Turkmenistan oasis of Panjdeh and Merv, runs through deep limestone gorges. Agriculture is mainly limited to the narrow valley floors for most of the river’s course in Afghanistan. [6] Badghis, the plateau region between the Murghab and Hari Rud watersheds, is the most important pistachio-growing area in Afghanistan. Badghis is also one of the most remote and inaccessible regions in the country. It also grows rain-fed wheat and is known for breeding hardy horses and ponies. [6] Many rural communities in the foothills of the Tir Band-i Turkistan and northern Afghanistan practice transhumance. They move to the upper valleys between May and September, where they live in yurts, or beehive-shaped felt tents, while there is pasture and water for their animals. The elderly, young children, and pregnant women stay behind in the settlements to tend to the houses and crops. [6]

The Helmand-Arghandab river basin is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, and it is located in the south and southwest. [7] Kandahar, the former capital of the Durrani kingdom, is located between the Arghandab and its tributary, the Tarnak. It also sits on ancient trade routes that connect Sind and the Indus with Herat, Persia, and Central Asia. Kandahar also benefits from its proximity to Karachi, which is Afghanistan’s closest city to a port and through which the majority of the country’s imports and exports pass. Kandahar is also near the Pakistan railhead at Chaman. [7]

The provinces of Farah, Nimroz, and southern Helmand in southwest Afghanistan are mostly barren deserts. [8] These areas are sparsely populated, and agriculture is mostly confined to the banks of the Farah, Khash, and Helmand rivers, as well as the irrigated areas around Giriskh and Lashkargah. The Sistan Desert, a triangle of land between Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, is a major smuggling route for opium and other high-value goods between Iran and Pakistan and is crisscrossed with truck tracks. [8]

Zaranj and Zabul are at the tail ends of the Helmand and Farah rivers, where they create shallow lakes that provide irrigation for farmers on both sides of the Iran–Afghanistan border. Riparian rights to these waters and the Sistan have been a source of contention between Iran and Afghanistan for over two centuries, and the dispute over the British-demarcated Sistan frontier is still unresolved. [8]

Afghan Dynastic History

There have been many dynasties throughout Afghan history.

The modern history of Afghanistan generally considers 1747 as the founding date of the modern state. In that year, Ahmad Shah, a young Afghan of the ‘Abdali tribe (who later adopted the regnal name of Durrani), established an independent kingdom in Kandahar and founded a monarchy that, in one form or another, ruled Afghanistan until 1978 [1]. However, the history of Afghan rule in the Iranian–Indian frontier can be traced back many centuries before the birth of Ahmad Shah [1].

The dynasty that Ahmad Shah founded in 1747 lasted only until 1824 when his line was deposed by a rival ‘Abdali clan, the Muhammadzais. The Muhammadzais were descendants of Ahmad Shah’s Barakzai wazir, or chief minister [2]. In 1929, the Muhammadzais, in turn, were deposed, and following a brief interregnum, another Muhammadzai dynasty took power, the Musahiban [2]. This family was the shortest-lived of all three of Afghanistan’s ‘Abdali dynasties: its last representative, President Muhammad Da’ud Khan, was killed in a Communist coup in April 1978 [2]. All of these dynasties belonged to the same Durrani tribe [2].

While dozens of tribes call themselves ‘Afghan’ (a term now regarded as synonymous with Pushtun), Afghanistan’s dynastic history is dominated by two tribal groupings: the ‘Abdali, or Durrani, and the Ghilzai [3].

The Ghilzai, or Ghilji, as a distinct tribal entity can be traced back to at least the tenth century when they are referred to in sources as Khalaj or Khallukh [3]. At this period, their main centers were Tukharistan (the Balkh plains), Guzganan (the hill country of southern Faryab), Sar-i Pul and Badghis provinces, Bust in the Helmand, and Ghazni [3]. Today, the Ghilzais are treated as an integral part of the Pushtun tribes that straddle the modern Afghan–Pakistan frontier, but tenth-century sources refer to the Khalaj as Turks and “of Turkish appearance, dress and language”; the Khalaj tribes of Zamindarwar even spoke Turkish [3]. It is likely that the Khalaj were originally Hephthalite Turks, members of a nomadic confederation from Inner Asia that ruled all of the country north of the Indus and parts of eastern Iran during the fifth to the early seventh centuries CE [3].

In 1150, Ghazni was destroyed by the Ghurids, a Persian-speaking dynasty from the hill country of Badghis, Ghur, and the upper Murghab, and by 1186, all vestiges of Ghaznavid power in northern India had been swept aside [4]. The Ghurids incorporated the Khalaj ghulams into their army, and it was during this era that they (and probably the tribes of the Khyber area) began to be known as Afghan, though the origin and meaning of this term are uncertain [4]. Possibly, Afghan was a vernacular term used to describe semi-nomadic, pastoral tribes, in the same way that today the migratory Afghan tribes are referred to by the generic term maldar (herd owners), or kuchi, from the Persian verb “to migrate” or “move home” [4]. It was not until the nineteenth century, and under British colonial influence, that Afghans were commonly referred to as Pushtun or by the Anglo-Indian term Pathan [4].

The rise of the ‘Abdalis to political prominence as clients of a Persian, Shi‘a monarchy has been largely airbrushed out of modern Afghan historiography and ignored by Western historians [5]. For many Afghans, especially monarchists, it is an embarrassment, for from the early twentieth century successive governments deliberately promoted a national identity constructed on three foundations: the Durrani dynasty’s adherence to Hanafi Sunnism, which was on occasion accompanied by anti-Shi‘a and anti-Persian sentiment; Pushtunness and the Pushtu language; and Afghan resistance to, and independence from, the dominant imperial powers of the region, including Persia [5]. One reason for Afghan historians favouring 1747 as the foundation of modern Afghanistan is that it avoids referring back to the previous two-and-a-half centuries of the Saddozai–Safavid alliance [5]. It also avoids the uncomfortable fact that prior to 1747 Kandahar (which Afghan monarchists would later promote as the dynastic and spiritual capital of Afghanistan) was for many decades an integral part of the Persian province of Khurasan, and that the ‘Abdalis were a Persianate tribe [5].

The Saddozai sultanate of Herat lasted for a mere fifteen years and was marked by a bloody power struggle between the Khudakka Khel and Sarmast Khel clans [6]. In all, seven sultans had come and gone: of these three had died at the hands of their own kinsmen, as had one heir apparent and several other clan members [6].

It was nearly two-and-a-half centuries before a Ghilzai once again became head of state of an Afghan kingdom. Following the Marxist coup of April 1978, Nur Muhammad, a Taraki Ghilzai from the Ghazni area, become president, and since then three other Ghilzais have ruled the country, however briefly [7]:

- President Hafiz Allah Amin (ruled 1979) was a Kharoti Ghilzai

- President Najib Allah Khan (who was President from 1987 to 1992) came from the Ahmadzai Ghilzai tribe

- Amir Mullah ‘Omar, head of the Taliban (ruled 1996–2001), belonged to Mir Wa’is Hotak’s tribe

Another prominent Ghilzai is Gulbudin Hikmatyar, head of the Hizb-i Islami militia, who was Prime Minister of Afghanistan during the Presidency of Burhan al-Din Rabbani [7].

It is commonplace to state that Ahmad Shah’s assumption of kingship marked the foundation of modern Afghanistan, but this too is an anachronism [8]. As far as Ahmad Shah and his contemporaries were concerned, Afghanistan was the territory dominated by the autonomous Afghan tribes, the Pushtun tribal belt which today lies either side of the Afghan–Pakistan frontier, and a region which, in 1747, was mostly outside of Ahmad Shah’s authority [8].

Imperial and Afghan nationalist-monarchist discourse claims the foundation of modern Afghanistan began with the ‘election’ of Ahmad Shah Durrani in Kandahar in 1747 and has tended to emphasize the Afghanness, or Pushtunness, of the dynasty [9]. This narrative ignores key historic factors that gave rise to this Durrani dynasty, while glossing over the uncomfortable fact that the ‘Abdali tribe and its dynasties were essentially Persianate [9].

When the Saddozai dynasty was finally swept aside by the Muhammadzais, they inherited the structural flaws of their predecessors [10]. Amir Dost Muhammad Khan was more ‘hands-on’ when it came to the administration of justice, but by placing all power in the hands of members of his own clan, he created a kingdom akin to an Arab sheikhdom, run more as a family enterprise than a nation-state [10]. The Muhammadzais too were plagued by sibling rivalry, and as with the Saddozais, the country was often plunged into civil war [10].

The sources include tables listing the principal dynasties of Afghanistan:

- 555 BCE–1001 CE [11]

- 664–1256 [12]

- 1256–1859 [13]

The sources also include a table listing the Hotaki dynasty of Kandahar and Persia, 1709–38 [14] and a table listing the Saddozai Kings and Barakzai Wazirs (Sardars) of Afghanistan, 1793–1839 [15].

Islam in Afghanistan

Almost all Afghans are Muslims, with a tiny minority adhering to other religions. [1] The 2004 Constitution designates Afghanistan as an Islamic Republic. [1] Since the 1920s, the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, one of four Sunni legal schools, has heavily influenced Afghanistan’s legal code. [1]

The majority of Afghans are Sunni Muslims. [2] Shi‘a and Isma’ili Muslims constitute a significant minority. [2] The Hazaras are primarily Shi‘a, with a smaller Isma’ili population. [2]

Sunni and Shi‘a Islam differ in theological beliefs and some ritual practices. [3] The main division between them stems from the dispute over who should have succeeded the prophet Muhammad. [3] Sunnis believe that the right to succeed Muhammad went to the four Rightly Guided Caliphs, while Shi‘as and Isma’ilis believe the right was bestowed upon Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, and his descendants. [3] The descendants are known as Imams. [3]

A civil war broke out after Muhammad’s death due to the dispute over succession. [3] During the war, ‘Ali and his son Hasan were assassinated. [3] ‘Ali’s other son, Husain, was killed in battle. [3] After these events, the Shi‘a split regarding succession to the Imamate: Isma’ilis recognize seven Imams, while Shi‘as recognize twelve. [3] The bitterness from these early disputes continues today. [3] Shi‘as ritually curse the first three Caliphs during prayers, which Sunnis find deeply insulting. [3] Tensions increase during the month of Muharram when Shi‘as and Isma’ilis mourn the death of Imam Husain during the ten-day ‘Ashura’ festival. [3]

Although the pre-Islamic heritage of Afghanistan is limited, it still influences popular culture. [4] Pilgrims walk around shrines, much like Buddhists once did. [4] The flags and banners at ziyarats come from Buddhist and Hindu traditions. [4] Some shrines are built on or next to Buddhist or other pre-Islamic sacred sites. [4]

Afghanistan’s Recurring Conflicts

Political conflict in Afghanistan has been a recurring theme throughout its history. One of the main sources of conflict has been the struggle for power between different tribes and clans.

- The sources provide many examples of this, such as the conflict between the Barakzais and Saddozais in the 18th and 19th centuries [1-3],

- the rivalry between different factions within the Durrani tribe during the reign of Ahmad Shah [4, 5],

- and the power struggles between siblings within the Muhammadzai dynasty [3, 6, 7].

Another major factor contributing to political conflict has been the role of centralized government. Afghan tribes have traditionally been fiercely independent and resistant to any form of central authority [8].

- This has made it difficult for rulers to establish and maintain control over the country, leading to frequent rebellions and uprisings [7-12].

Foreign interference has also played a significant role in Afghan political conflicts.

- The sources highlight the involvement of Britain, Russia, and the United States in Afghan affairs, often exacerbating existing tensions and contributing to instability [13-35].

The competition between these external powers for influence in Afghanistan has led to a series of proxy wars and interventions, further fueling conflict and undermining efforts at peace and stability.

Ideological differences have also contributed to political conflict.

- The rise of Islamism in the 20th century, particularly the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, has led to tensions between those who seek to establish an Islamic state based on Sharia law and those who support more secular forms of government [31, 36-43].

This ideological divide has been further exacerbated by the emergence of Marxist-Leninist groups, such as the PDPA, leading to clashes between communists and Islamists [38, 39, 44].

The sources also highlight the role of personal ambition and rivalry in Afghan politics.

- Individuals have often put their own interests above those of the nation, leading to betrayals, power grabs, and assassinations [1, 5, 45-48].

The prevalence of corruption and the lack of accountability have further undermined trust in government and exacerbated political conflict.

The issue of Pushtunistan, the demand for self-determination for the Pushtun tribes living on both sides of the Afghan-Pakistan border, has also been a major source of tension and conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan [49-58].

Afghanistan’s political history has been marked by a complex interplay of these factors, resulting in a cycle of violence and instability. The sources suggest that the country’s deep-rooted ethnic, tribal, and ideological divisions, combined with external interference and the lack of a strong and inclusive political culture, have made it difficult to achieve lasting peace and stability.

By Amjad Izhar

Contact: amjad.izhar@gmail.com

https://amjadizhar.blog

Affiliate Disclosure: This blog may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you click on the link and make a purchase. This comes at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products or services that I believe will add value to my readers. Your support helps keep this blog running and allows me to continue providing you with quality content. Thank you for your support!

Leave a comment